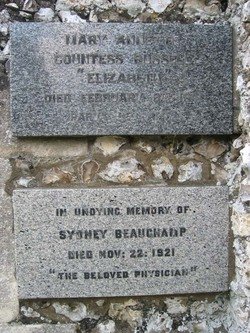

In front of St Margaret’s church, by the large war memorial beech tree, is a white gravestone ‘In Memory of Constance Elfrida Ingpen’. Not an instantly recognisable Tylers Green name. The inscription continues, ‘Devoted wife of Walter de la Mare, Loving mother of her four children, 20 Sept 1861 – 10 July 1943’.

In front of St Margaret’s church, by the large war memorial beech tree, is a white gravestone ‘In Memory of Constance Elfrida Ingpen’. Not an instantly recognisable Tylers Green name. The inscription continues, ‘Devoted wife of Walter de la Mare, Loving mother of her four children, 20 Sept 1861 – 10 July 1943’.

How did Walter de la Mare’s wife come to be buried in St Margaret’s churchyard?

Constance Elfrida Ingpen and the 20 year old Walter de la Mare met at the Esperanza drama group in Wandsworth in 1893.

Elfrida was their leading lady, the star of their productions, and Walter or ‘Jack’ (from his middle name John) was a junior clerk with the Anglo-American Oil company (later to become ESSO), and an aspiring author. In May 1894 Jack and Elfrida took leading roles in a play written by Jack, and although Elfrida was more than 10 years older than Jack they soon became an ‘item’. Elfrida, affectionately known as ‘Elfie’, had a hard childhood after both her parents died, she had been previously engaged, but her fiancée had died before they were married.

Walter and Elfie didn’t rush into marriage, mainly for financial reasons, and it wasn’t until the 4th August 1899 that they were married quietly at Battersea parish church. Walter continued working for Anglo-American until 1908 when his writing was producing enough income to support his wife and family of four small children.

They lived at various addresses in London and in 1925 moved to Hill House in Taplow which was to be their home until 1939. Hill House now has a blue plaque.

In September 1939 Elfrida suffered a pulmonary embolism, only days after war had been declared. Elfrida and Walter were invited by their eldest daughter Florence and her husband Rupert to stay with them at the Old Park, Hammersley Lane, for Elfrida to convalesce. Walter and Elfrida gave up Hill House, and moved their home to a flat in Twickenham where they thought Elfrida would be better able to manage as her health improved. Unfortunately she never fully recovered and also developed Parkinsons Disease. Elfrida and Walter spent most of their time living with Florence and Rupert at the Old Park to be safe from the constant air raids on London.

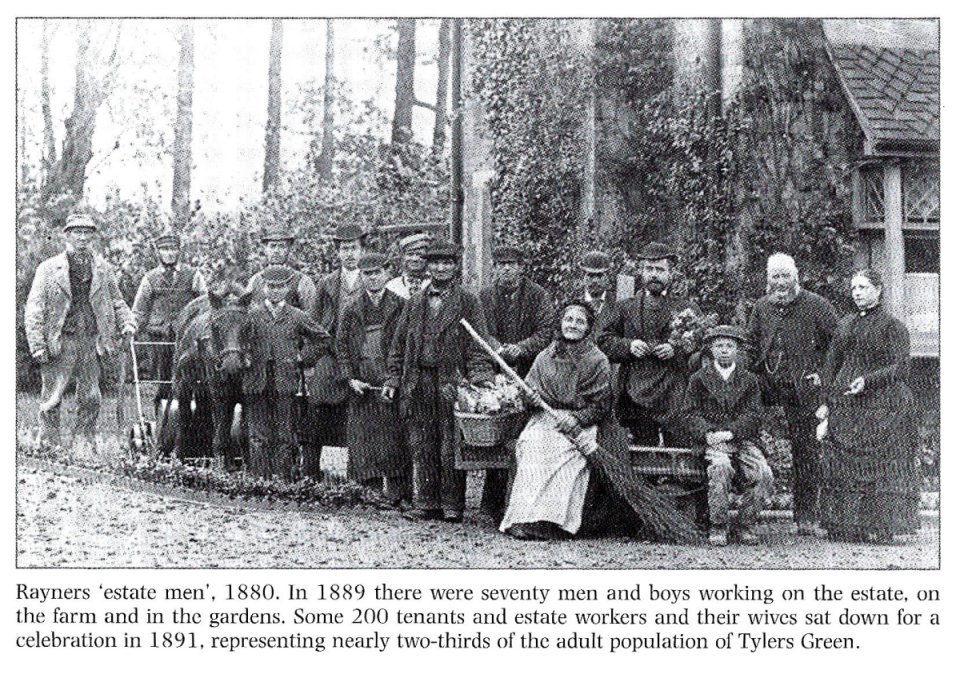

The 1939 register shows 20 people living at the Old Park. Florence and her husband Rupert Thompson and their children, four domestic staff, Walter and Elfrida and three other aged Ingpen relations, plus a school teacher and three children with different surnames, presumably evacuees. Their neighbour at Rathenrae, (now Folly Meadow), across Hammersley Lane, the Indian princess Sophia Duleep Singh also had three evacuee children. Their next-door neighbour at Colehatch House was Sophia’s sister Catherine. After her sister’s death in 1942, Sophia renamed Colehatch House to Hilden Hall as a tribute to her sister, Hilda was Catherine’s middle name, although another suggestion is that it was named after a place where they had lived in Germany.

Elfrida died on the 10th of July 1943, and was buried at St Margaret’s. A little known connection between Tylers Green and Walter de la Mare and his family. Walter died in 1959 and is buried in St Paul’s Cathedral where he was a choir boy.

Acknowledgements to the excellent biography of Walter de la Mare, by Theresa Whistler which has a few photographs taken at the Old Park, although the original house was completely rebuilt a few years ago in a very modern style.

Peter Strutt, St. Margarets and Holy Trinity Penn Parish Newsletter, February 2018

(Elfrida and Old park photographs from ‘The Life of Walter Delamere’, Theresa Whistler)

An extract from the biography of ‘Sophia’, by Anita Anand, p.367.

‘One time in 1942 I think, we were late back … The princess was waiting for us as usual, and demanded to know where we had been,’ recalled Shirley (the eldest evacuee child). ‘We told her a nice old man had stopped us on the way home and wanted to know all about us … She was furious. She told us never to talk to strangers again, and got straight on the phone to the local policeman. She must have given him quite the earful because he was off on his bike immediately, huffing and puffing up and down the lane to investigate. It turned out the old man was Walter de la Mare, who was staying with his daughter in Penn. He was working on a poem about evacuees. We felt terrible for the trouble we caused for him. Poor man got the fright of his life!’