Kindertransport

Part 1 – The Tylers Green Hostel for Jewish refugee boys

Around the turn of 2014, I was alerted by Hilary Forbes to a programme on the BBC News 24 (channel 80) – called Kindertransport: Journey to Life. It was a 30 minute account of the British Government-sanctioned mission to bring 10,000 Jewish children to England following Kristallnacht in November 1938, after which it was obvious that children from Nazi Germany, Austria, Poland and Czechoslovakia were at great risk. In the nine months preceding the outbreak of war these children were placed in foster homes schools, farms and hostels all over England.

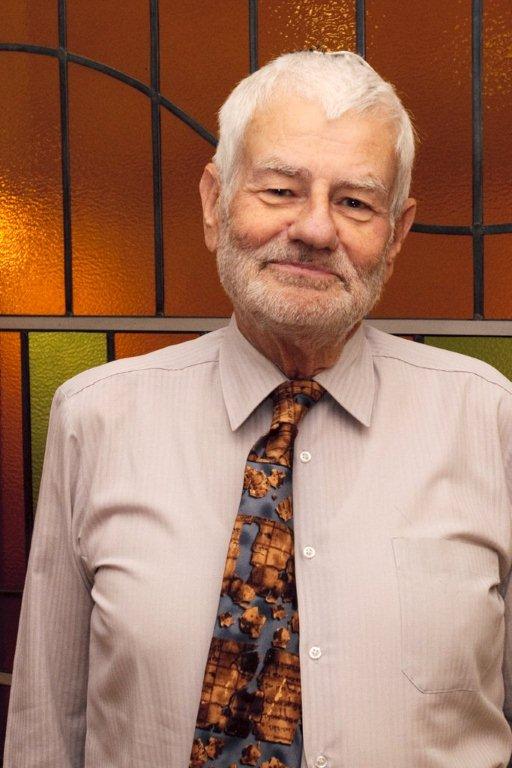

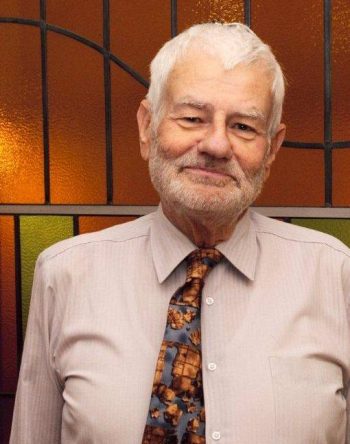

One of those who spoke in the film about his experiences was the Rev. Bernd Koschland, a distinguished elderly man who was pictured sitting by our Widmer Pond and standing outside the gate to St Margaret’s Church. He turns out to be a Jewish minister and the Editor of a journal called Kindertransport. He was born in Nuremburg in Germany in 1931 and was just eight when he came to England in April 1939 unable to speak English. He never saw his parents again. He spent his first 18 months in a Jewish hostel in Margate which housed 60 boys from eight to sixteen and was transferred to a hostel in Tylers Green in 1941

He spent four years living in Tylers Green between 1941-45 and went to the Tylers Green primary school on School Road (which is now split into the First & Middle Schools) and then on to the Royal Grammar School. There were some 66 wartime Jewish hostels in the UK and the records of many have been lost, but it is our particular good fortune that he holds the archive on the Tylers Green hostel has written in detail about his time here.

I have spoken to him on the telephone and he gladly agreed to my putting a condensed version of his article as a series in Village Voice . He was very pleased to hear from someone from Tylers Green because he remembers his time here with great affection and says he feels very much a Tylers Greenian! It was a lovely, peaceful place to be. It made his life sane and was the best he could have had in the circumstances of war time and in the absence of his parents.

I have spoken to him on the telephone and he gladly agreed to my putting a condensed version of his article as a series in Village Voice . He was very pleased to hear from someone from Tylers Green because he remembers his time here with great affection and says he feels very much a Tylers Greenian! It was a lovely, peaceful place to be. It made his life sane and was the best he could have had in the circumstances of war time and in the absence of his parents.

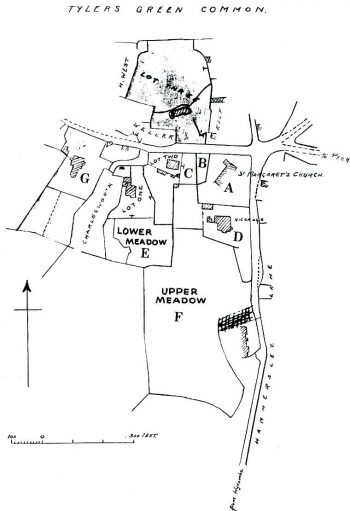

The hostel was housed in the original Vicarage for St Margaret’s. It was a large house, built in 1865 with seven bedrooms, three reception rooms, coachhouse and stables with farm buildings and piggeries added later. It also had a huge garden known as Vicarage Meadow (shown as Upper Meadow on the plan), which now lies behind the Hammersley Lane houses, part of which is now the graveyard extension. The Rev. Gerald Hayward, who was Vicar of Tylers Green from 1918 to 1951, never lived in the vicarage because it was too large and expensive to maintain so he let it and lived elsewhere. It was presumably requisitioned by the government at the outbreak of war. In 1960, it was pulled down and a new, smaller vicarage was built, but that too was demolished in 2004. During the war Mr Hayward was not only the landlord for the hostel, he was also the local Billeting Officer.

Miles Green, Village Voice 160, February 2014.

Part 2 – Setting up the hostel

In 1939, after receiving pitiful letters from parents begging them to bring their children out of Germany, the Jewish community of Golders Green under their spiritual leader, Rabbi Dr Eliyahu (Eli) Munk, decided to open a hostel, and a Hostel Committee was formed in January 1940. They later also opened a hostel for girls at Great Chesterford near Cambridge. Both hostels were visited regularly by Committee members who dealt with the various government departments and raised funds. The Tylers Green hostel opened in February 1940, with places for a maximum of 25 boys. Vacancies were quickly filled, with frequent applications for new admissions. Applications might be rejected because of lack of space or because the child was too young or not orthodox enough. Bernd’s sister, who was living with a family in South London, obtained his admission on the grounds that he might get lost as a Jew in the village where he was evacuated

There were difficulties initially in enlisting and retaining staff, but Mr and Mrs Max Baer were appointed in January 1941 as wardens, at £3 weekly with two lady helpers at £1 each, and domestic help at 15 shillings. The Baers stayed until the War in Europe ended, after which they emigrated to the United States. They proved excellent and had a lasting influence on many of the boys. Mr and Mrs Woolf were appointed as teachers and the four of them were known fondly to the boys as ‘The Zoo’.

The problems of finding suitable staff were compounded by the fact that people of German or Austrian origin were classed as enemy aliens and had to obtain Home Office permission to work. They also needed to register with the police. Furthermore, Tylers Green was a protected area and thus two of the boys who were over sixteen had to leave because they were enemy aliens without permission to remain in the area. Both were interned but later released. Boys under sixteen were not affected. A journey from Tylers Green to High Wycombe also meant entering a protected area, requiring police permission

Letters in the archive express concern over illness or emotional and social difficulties. Bernd Koschland points out that many of the children had changed home between 2 and 9 times. In some cases one or both parents were missing in Europe or only one had survived. In others, one or other parent was invalid or had died, or was living abroad or serving in the Forces. He himself had moved eight times since leaving Germany, including twice for a few weeks only. Attempts were made to help one older boy who caused severe discipline problems, which continued even after he had left. Some found it difficult to adjust, not just because they were refugees or evacuees, but because of problems in their home. Letters report how one parent might be in the Forces and the other unwell, or both in the Forces, or one in the Forces and the other on war work, leaving no one to care for a child. In one case, both parents were mentally unwell. Problems were caused also by divorce, although this was a rarity.

Miles Green, Village Voice 161, April 2014.

Part 3 – Religious Orthodoxy

The Refugee Children’s Movement, the overall organisers of Kindertransport, regarded the ‘spiritual life of the child as the foundation of its well-being’ and despite criticism took steps to ensure this. Orthodox religious practice was central to the ethos of the Tylers Green hostel and was expected of boys and staff irrespective of their previous religious experiences. The Prayers were conducted three times daily by the boys themselves, including reading from the Torah, Bernd Koschland observes that ‘this was a useful preparation for adult life and an influence on my becoming a Minister. Servicemen and others from the area would join us for services especially on Shabbats (Saturday, the Jewish day of rest) and festivals, since we were the nearest ‘synagogue’. Jewish studies took place daily, and on Shabbat for three hours.’

Rabbi Dr Eliyahu Munk played a leading role in the hostel management and ‘He was particularly admired by the youngsters of Tylers Green where he always made himself available to individual pupils, though he did not take individual classes. The respect accorded him reflected the genuine interest that he took in their welfare – material as well as spiritual; to him they were not cases but individual human beings with individual problems, and to them he was not a remote benefactor but a palpable and caring presence.’ After the War he went as an emissary to Europe, bringing relief to survivors of the camps for some eighteen months.

Rabbi Munk’s reasonable approach was a major factor in ensuring that uprooted Kindertransport children remained practising Jews rather than being lost to the Jewish community, as were many Kindertransportees. It has been estimated that only some 35 per cent of Kindertransport children remain actively Jewish in this country. Evidence of low attachment to Judaism is clear also from autobiographies of Kindertransportees. It was agreed that parents had to be informed of the orthodox religious character of the hostel and their need to adhere to it. No boy could be accepted who worked on Shabbat. Bernd Koschland’s sister, staying with a family in South London, invited him to come for Passover in 1943, but correspondence indicates the reluctance of the Committee and warden to let him go, since they viewed the family as not fully observant. The warden of the girls’ hostel, expressed concern about a girl who was receiving instruction in Christianity at school and said the Lord’s Prayer daily.

Rabbi Munk and the Committee requested that those children who attended the Royal Grammar School at High Wycombe be excused lessons on Shabbat morning, to which the Headmaster reluctantly agreed. Mr Baer, the warden, was also concerned also that children should not walk further than the permitted distance on Shabbat.

Observance of the dietary laws posed particular problems. Rabbi Munk ruled that the hostel could not purchase kosher meat in High Wycombe, since it did not meet the required standards. The hostel therefore purchased acceptable meat from Golders Green which was normally sent by train or occasionally fetched by boys. If it ever went astray, meatless days followed.

Miles Green, Village Voice 162, June 2014.

Part 4 – Paying for the hostel in Hammersley Lane

The financial records of the hostels, shows that the committee worked on a tight budget. Besides payments from the Government and from organizations responsible for boys and girls or from their parents, they relied on donors and voluntary subscriptions, mainly from members of the Golders Green Jewish community. From the Government’s billeting allowances each evacuee child was allocated 1s 4d weekly, comprising 6d pocket money including stamps, 1d haircutting and 9d shoe repairs. Within about six months pocket money went up by 1d because of a rise in postage. The Government allowed 10s per child per year for medical attention and medicines, but the local doctor was unhappy and further payments were later agreed. The few boys who worked, of whom there were four in October 1940, were allowed 5s for pocket money and 3s for clothing, and contributed the rest of their wages for board.

Budgeting was further complicated by the need for all kinds of permits and priority permits, such as for goods, repairs and the transfer of boys to Tylers Green. Billeting allowances could vary according to status, and the Ministry of Health did not regard Tylers Green as an entirely evacuee hostel. Payments for evacuees were mostly 25s to 30s per week for the individual.

Since income was lost when boys left the hostel, it was vital to have a full complement of residents. Appeals for clothing were made to the Jewish community. To save money, socks were darned in the hostel from November 1943, rather than by outsiders.

Donations were often in kind rather than financial, and in the form of furniture, radios, books, magazines, games, treats or outings. Tylers Green was given three new bicycles, for example, which had also to be maintained, ‘a useful skill later in life’, observed Bernd Koschland, ‘when my only mode of transport was a bicycle’.

Various communities and organizations are recorded in the archives as donors. Jewish communities in Beaconsfield and High Wycombe gave assistance and treats. Local Borough Councils and official bodies such as the Ministry of Health and Work helped on several occasions. Individual donors included Baron James de Rothschild who had opened Waddesdon Manor, near Aylesbury, to 26 boys.

Close attention was paid to boys’ and girls’ welfare, especially in helping them to find work. One boy worked with the Jewish Chronicle, then located in High Wycombe. Another boy was found work in a local grocery store and another left Tylers Green to work as a cabinet maker in London earning £2 per week.

Miles Green, Village Voice 164, October 2014.

Part 5 – School

Correspondence with parents, with the Children’s Refugee Committee and others, reflects careful planning for the children’s future, for appropriate schooling during and after the War and for the need to provide proper training for future careers

Boys attended local primary and secondary schools as well as technical colleges. Encouragement was given to take part in local primary-school activities, such as a poster competitions on behalf of ‘Wings for Victory’ or ‘Warship Week’, with prizes ranging from 1s to 11s. A Koschland warship with upturned saucepans for guns even won a prize! Termly and shorter fortnightly school reports were carefully examined by Mr Baer, who reported back to the committee.

Children from the hostel would not automatically be accepted at the local Royal Grammar School. Even after passing the eleven-plus examination, Buckinghamshire Education Committee insisted that fees be paid, that aliens be allocated to classes according not only to their age, but their command of English, and that no English boy would be excluded at the expense of an alien.

Children from the hostel would not automatically be accepted at the local Royal Grammar School. Even after passing the eleven-plus examination, Buckinghamshire Education Committee insisted that fees be paid, that aliens be allocated to classes according not only to their age, but their command of English, and that no English boy would be excluded at the expense of an alien.

Bernd Koschland remembers that ‘four children from my Tylers Green Primary School passed the eleven-plus, two of them local, a third from London, and myself, but only once the conditions had been met. Several Tylers Green boys eventually went to the school, but funding of five guineas a term remained a problem for the Committee.’ Bernd’s fees were met by an anonymous member of the Jewish community. The Royal Grammar School offered an excellent education, although the regular staff were away in the Forces, and he is very proud of being an old boy of the school.

‘Kennedy’s Latin Primer is still embedded in my mind, and I participated in the Army Cadets (I can still feel the weight of the Lee Enfield .303 rifle) and the Aircraft Spotters Club (we aspired to distinguish a Heinkel from a Hurricane) and learned to play fives according to the Eton Rules. We had jam sandwiches for lunch in which the jam had soaked into the bread.’

‘Kennedy’s Latin Primer is still embedded in my mind, and I participated in the Army Cadets (I can still feel the weight of the Lee Enfield .303 rifle) and the Aircraft Spotters Club (we aspired to distinguish a Heinkel from a Hurricane) and learned to play fives according to the Eton Rules. We had jam sandwiches for lunch in which the jam had soaked into the bread.’

Miles Green, Village Voice 165, December 2014.

Part 6 – The hostel as a home

While a hostel could barely replace a normal home, it was the nearest thing available under the circumstances. Mrs Rosenfelder, the Hostel Committee’s Secretary, who was looked up to as a mother-figure, wrote ‘the atmosphere was one of a home, not just a hostel, in which we endeavoured to compensate the boys for the loss of their own home and for the loss of their parents’. Bernd Koschland observes that ‘ Norms have changed and some punishments would be unacceptable today, such as Mr Baer’s Ohrfeige, ‘boxing of the ears’. On birthdays and Barmitsvahs gifts were given. There were treats on Shabbat and festivals, and a highlight of the week was the sweet ration, sometimes withheld as a punishment. The vast gardens were ideal for building secret hideaways or just for peace and quiet.’

Life at the Hostel was as normal as circumstances allowed. The ample grounds of the Old Vicarage at Tylers Green (marked Upper Meadow & F on the plan) provided room for football, cricket and wide games. There were also indoor games, as well as books and magazines. Boys helped with washing up and took turns peeling potatoes for the week into a large zinc bath. There was time for reading, writing letters, preparing for the services and socializing, and rotas were arranged for weekly baths and more occasional haircuts at the local barber.

Frequent visits from families or friends made us feel less isolated, and from early in 1944, visitors were no longer required to have permits for coming to Tylers Green. Visiting hours were from 2 pm to 6 pm, with only two people visiting any child at one time. Visitors should not be younger than fourteen years old. In view of rationing, no meals would be served in the hostel, but a cup of tea would be obtainable at about 4.30. Visitors could bring food with them.

Miles Green, Village Voice 166, February 2014.

Part 7 – Closure of the Hostel

Closure of the hostel in the former Vicarage next to St Margaret’s Church in Hammersley Lane was inevitable as the end of the war in Europe approached. The wardens and teachers, Mr and Mrs Baer and Mr and Mrs Woolf, left in May 1945. Mrs Rosenfelder, the Hon. Secretary of the hostel, who was a mother-figure for the boys, sent the following letter on 26 July 1945:

This is your last Shabbat at Tylers Green. Don’t just take it for granted. Think back over the years you have spent at the Old Vicarage and remember with gratitude that you have spent these days of war in peace and harmony, and those with whom you have lived there have done so very much to try replace your own homes and the care of your parents, of which you have been deprived. I hope you will remember Tylers Green and all that it stands for all your lives and wherever you may be in later years, let the years 1940-1945 have a place in your minds.I am looking forward to welcome you down in London. Shabbat Shalom to you all. Mrs C. Z. Rosenfelder

A request to keep the house for a further year was not accepted as it had already been let to another organization and so the hostel closed on 30 July 1945 and the children transferred to London.

Bernd Koschland concludes: “A few former Tylers Green ‘boys,’ now grandparents, still meet occasionally, or maintain contact with those abroad by email. The experience of Tylers Green formed a strong bond that has survived the years. For this we are grateful to the Golders Green Beth Hamidrash and its Committee, to the staff that cared for us and also to the various other committees and individuals involved in our welfare. Mrs Rosenfelder did not exaggerate when she wrote, ‘I think that our object, to achieve a real home for these boys has been achieved’.

I discovered my parents’ fate only in 1945, having tried but failed to contact them through the Red Cross. They had been deported from their home in Fürth to Riga and Izbika (Latvia), and then killed, as my sister Ruth heard from a survivor who had been with them. The parents of a few Tylers Green children survived and were reunited with their children after the War, but three brothers’ hopes were dashed when the adults thought to be their parents turned out to be people with an identical surname and to have come from the same region.”

Miles Green, Village Voice 167, April 2015.

Part 8 – Local memories of the Hostel

To conclude this series there are just a few local memories to record. In earlier Village Voices people have written about the War and many of them refer to the German Jewish boys living in the old Vicarage in Hammersley Lane. One English evacuee from London remarked that ‘they were worse off than we were because most had no idea what had become of their parents’. Sandra Mason remembered her husband Bill saying he had become friendly with one of the German Jewish boys in the orphanage at the top of Hammersley Lane.

Jean White (née Rolfe) wrote: ‘I well remember the boys from the German Jewish community in Hammersley Lane. I found a purse belonging to them. It was money to repair their shoes. As a small girl I was nervous but I returned the purse and a few days later at school I was rewarded with a brown paper parcel from one of the boys. It contained a jar of sweets (despite strict rationing) and a note which said “Honesty is the best policy”. This message is still with me and I am now 70 years old.’

Miles Green, Village Voice 168, June 2015.