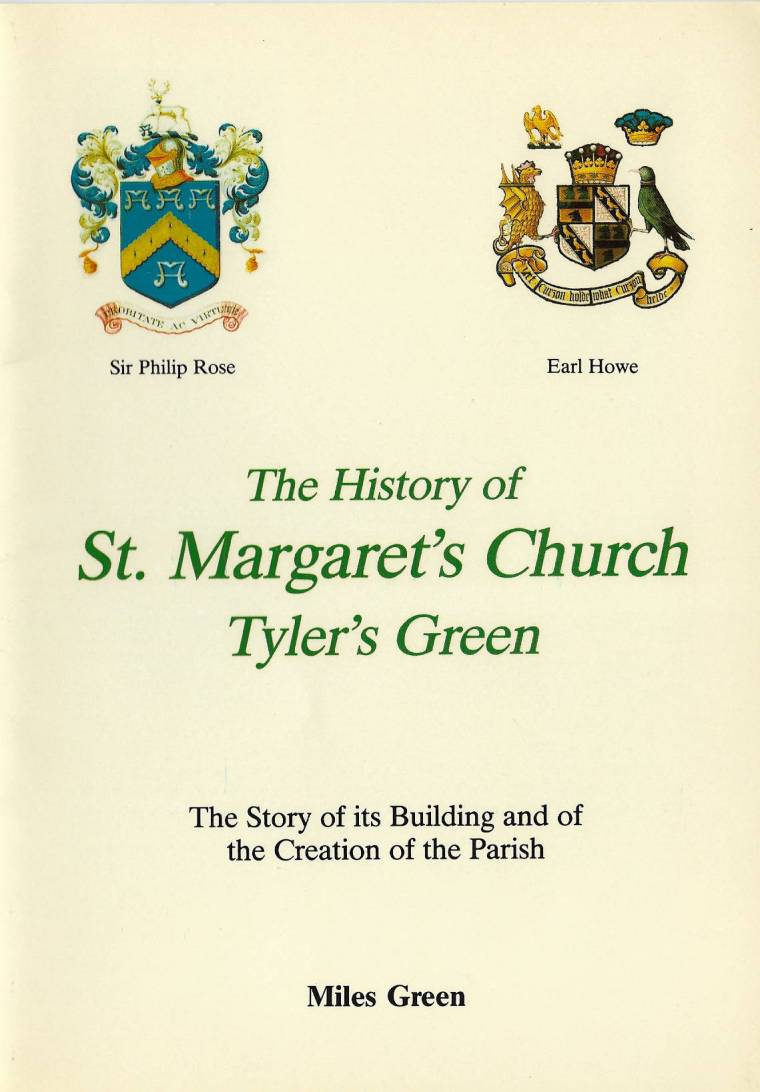

The History of St Margarets’s Tylers Green, Miles Green, July 1984

There is a condensed overview of this book at The building of St Margaret’s

PREFACE

PREFACE

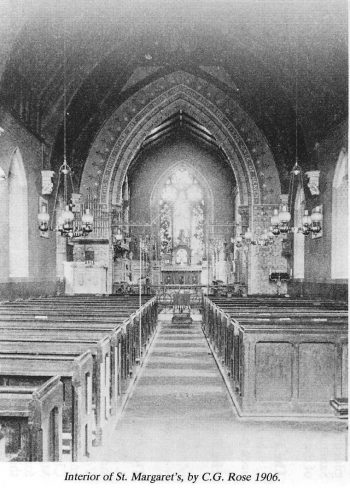

I came to the task of writing about St Margaret’s, half expecting to produce a rather pedestrian account of an unremarkable Victorian Church. Instead, I have found the story of its building to be an epic of its kind and the plain Church of my uninformed imagining has been transformed by my appreciation of the tremendous effort that attended its building and of the love and care of successive generations. In the words of the Diocesan Architect “This is a wholly admirable interior … it is clear that great care has been taken of this Church over a long period”. John Betjeman, our recently deceased Poet Laureate, was sufficiently impressed to describe the interior as rather striking. “One of the prettiest churches of the Anglican Faith in the County” wrote the second Sir Philip Rose, more partially.

I have been fortunate. in having access to a very large volume of useful records and correspondence, of which this booklet represents only the bare bones and wish to record my thanks to those who have helped me in various essential ways: to our Vicar, Michael Hall, for his encouragement and for records from the Parish Office: to Ken Stevens, for most generously putting me on to the main body of existing documents: to Lady Joan Rose, for the Memoirs of the second Sir Philip Rose: to Mr D.A. Armstrong, Records Officer of the Church Commissioners, for his ready help and advice: to Dr Barratt at the Oxford Record Office and the Diocesan Registrar, for much useful information on the glebe properties and for permission to use the 1854 lithograph: to Brian Cullip, for the time and effort he put into taking and copying all the photographs, including a trip to Oxford: to the various owners of the photographs, for their permission to use them: to Mrs Evelyn Clark, for many good ideas and corrections and the intriguing information that one of the stained glass windows in the Church contains a spelling mistake: to Mike Curry, for his help with the maps: to Elizabeth Nalder Williams, for two useful press cuttings from Aylesbury: to my wife, for so quickly and skilfully typing all the drafts.

It did not seem necessary in a work of this kind to include detailed references to the source material, but if any reader wishes to follow up a particular line of enquiry I will be happy to help.

I am most grateful to St Margaret’s Church for funding half the printing costs and to Chepping Wycombe Parish Council for generously providing an interest free loan for two thirds of the balance.

Any profits will go towards the cost of putting shields, with the coats of arms of the Howe and Rose families, in the Church, and to local history projects.

Mrs Violet Becher was the first to write a booklet about St Margaret’s, in 1937, of which only a very few copies have survived, but there is not much overlap between our accounts since she concentrates on the detail of the interior. I have indicated where I have used her account unsubstantiated by independent sources. I would suggest that there is still a need for a much briefer pamphlet, more on the lines of Mrs Becher’s, that can be picked up at the door of the Church and used as a guide.

Miles Green Woodbine Corner July, 1984

The History of St Margaret’s Church Tyler’s Green

The Story of its Building and of the Creation of the Parish

CONTENTS

PART I

Introduction

Preliminaries

Getting Underway

Building

Laying the Foundation Stone

Problems

The Final Dash

Consecration

Afterwards

The Final Cost

PART II

Establishing the boundaries of St Margaret’s District

Building the Parsonage House

Glebe and Endowments

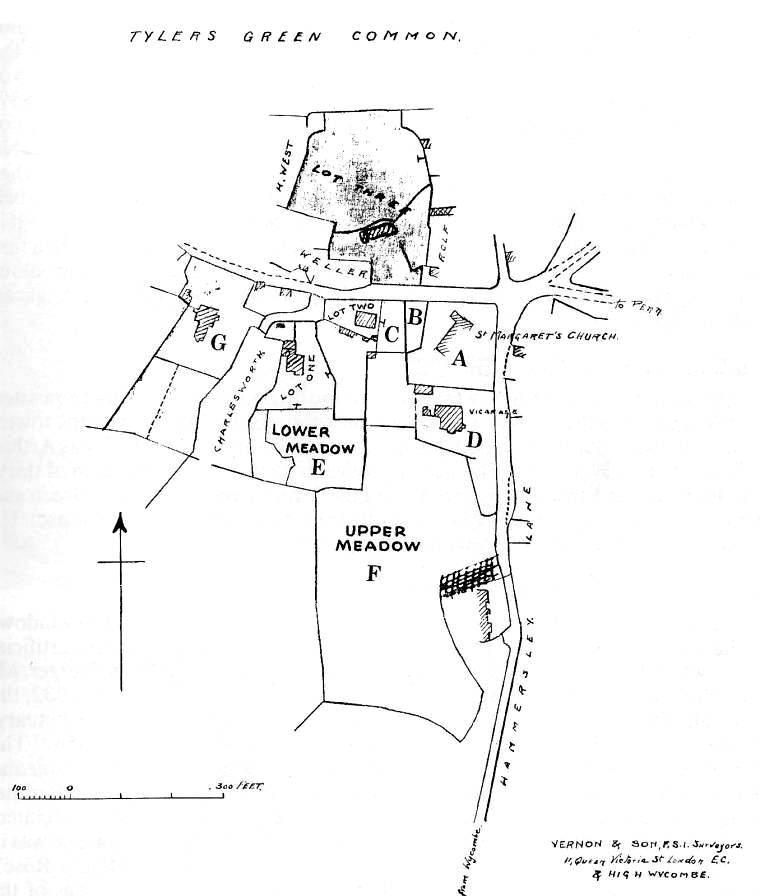

Plan of Glebe Property

Later additions and changes to the Church

Conclusion

The Vicars of St. Margaret’s 1854 – 2000

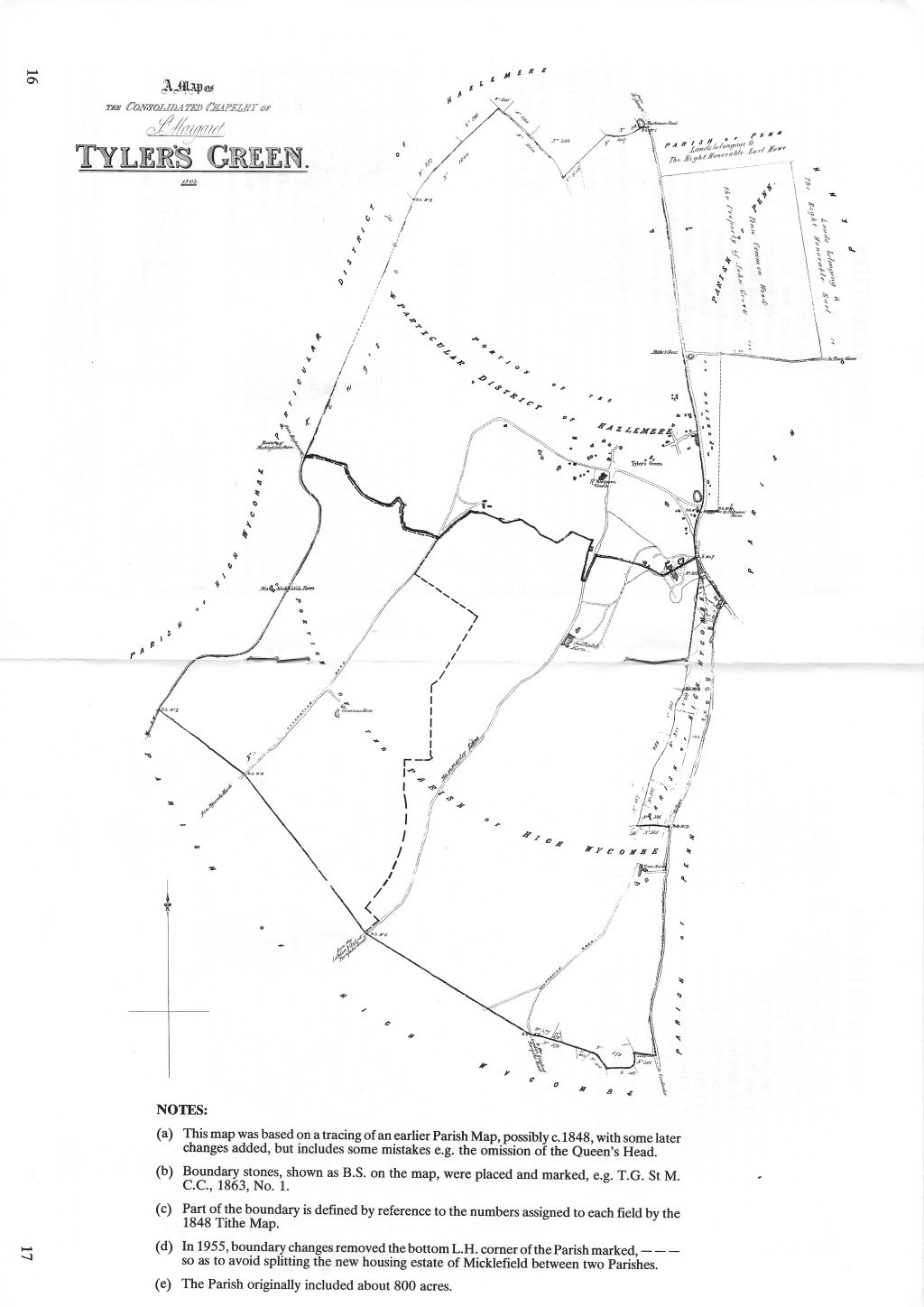

A Map of the Consolidated Chapelry of St. Margaret, Tyler’s Green, 1862

PART I

INTRODUCTION

WHEN Philip Rose arrived in Tyler’s Green, in 1845, he was a very successful, 29 year old London solicitor, who had already made a name for himself the previous year, by inspiring the building of the Brompton Hospital for Consumption and involving the Queen and half the House of Lords in the venture. He was also a close friend and legal adviser to Benjamin Disraeli and had made a good deal of money from his part in the endless legislation concerning the building of the new railways. He was very much a Wycombe man – for 9 out of 90 years, four generations of his family were Mayors of Wycombe, including his father and his elder brother William, who was to be Mayor in 1848. He bought Rayners Farm and in 1847 started building the present large house in its place, whilst steadily acquiring local farms and property, until he was soon the de facto Squire of Tyler’s Green. Disraeli had bought Hughenden Manor at the same time and both were enjoying the early pleasures of being landowners.

WHEN Philip Rose arrived in Tyler’s Green, in 1845, he was a very successful, 29 year old London solicitor, who had already made a name for himself the previous year, by inspiring the building of the Brompton Hospital for Consumption and involving the Queen and half the House of Lords in the venture. He was also a close friend and legal adviser to Benjamin Disraeli and had made a good deal of money from his part in the endless legislation concerning the building of the new railways. He was very much a Wycombe man – for 9 out of 90 years, four generations of his family were Mayors of Wycombe, including his father and his elder brother William, who was to be Mayor in 1848. He bought Rayners Farm and in 1847 started building the present large house in its place, whilst steadily acquiring local farms and property, until he was soon the de facto Squire of Tyler’s Green. Disraeli had bought Hughenden Manor at the same time and both were enjoying the early pleasures of being landowners.

For the first few years, Rose, who was a deeply religious man of a formidably puritan kind, went to Penn Church where he had permission to occupy Lord Howe’s pew. His son later recorded that his father never liked it much since “it was a dreary old church in those days1 with richly cobwebbed windows in the corners of which huge spiders lurked and a Service as dreary as the Church, the spiders being much more interesting than the Sermons”. It was not long before he started thinking about building a Church at Tyler’s Green, though perhaps as much to satisfy his squirearchical ambitions, as for the other more genuinely selfless reasons which he was to put forward.

In the first half of the 19th C., there was a fever of church building to cope with the large scale shift of population which was a consequence of the industrial revolution. The Church Building Commissioners had been set up in 1818 with £1 ½ million and the aim of building some 600 churches and creating new parishes for them. What we now think of as Tyler’s Green had been part of the large parish of Wycombe since before the Norman Conquest, but Wycombe’s rapidly increasing population required new churches and in 1845 a church was built at Hazlemere which included Tyler’s Green in its new Ecclesiastical District.

In 1849, Rose had dealt with the legal complexities of establishing a new Church and parish at Prestwood, of which Disraeli was Patron, and he must also have been very much aware of the new Church at Penn Street which Lord Howe had built the same year. Meanwhile he had been successfully master-minding the building and funding of a Chapel at the Brompton Hospital, which was finished in 1850.

- A far cry from the lovely old church which we see there today.

PRELIMINARIES

The Census

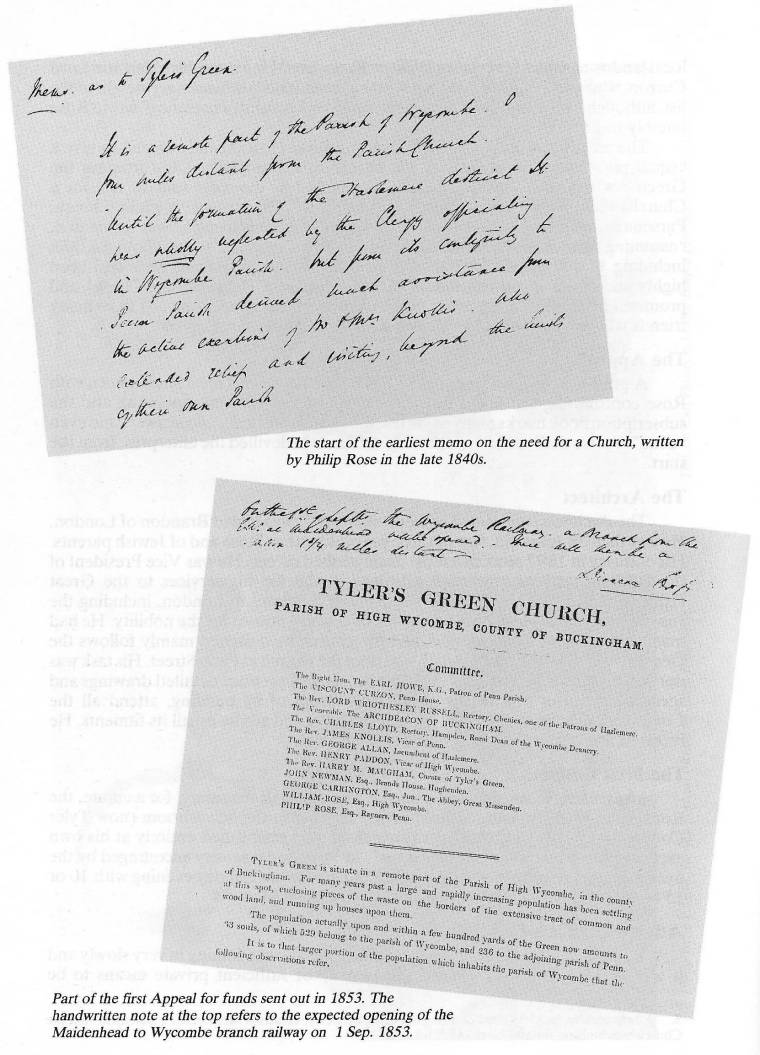

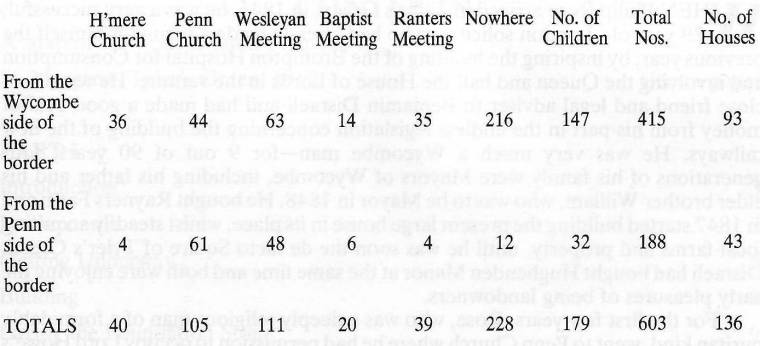

No one could therefore have been better qualified by both experience and enthusiasm, than Philip Rose, to set about building a Church and establishing Tyler’s Green as an Ecclesiastical District (later a Parish) in its own right. “There are few things I have so much at heart” he wrote. He started, probably in the late 1840s, by conducting a census “from actual enquiry of every house on the Green” into the new District. It’s conclusions were as follows:

Although the totals do not all add up correctly, they do show that over a quarter of the villagers were Wesleyan, Baptist or Ranters. The Wesleyans would have gone to their Chapel in Penn and the Ranters to theirs’ in Church Road, Tyler’s Green, both of which are still going strong. The Baptists had a Chapel on Beacon Hill of which only the graveyard remains. Rose was to make no mention of these Chapels in his subsequent appeal for funds for a new Anglican Church.

His main census, compiled a few years later, in January 1852, records much detailed information on every household, including the names of owners and occupiers, their ages, any lodgers, the size of the house and “whether a privy to each”. It totals 722 souls-made up of 496 from the Wycombe side and 226 from the Penn side which was a respectable number, especially since he was able to claim that numbers were increasing rapidly every year as a result of illegal enclosure on the Common.

Illegal Enclosures on the Common

The Common, or Waste, belonged to Bassetsbury Manor, which was held by the Dean and Canons of Windsor. Local inhabitants had certain rights of common and of pasture, but these did not include enclosing parts of it with hedges and then building cottages, as had been happening. “Within living memory Tyler’s Green was an open common without any house or building upon it”2, wrote Rose in 1854 “but small encroachments were from time to time made upon the Waste at the skirt of the great Wood (St John’s Wood, which used to come as far down as Wheeler Avenue) on which mud houses were afterwards built which have gradually given place to buildings of a more substantial character, until within 40 or 50 years a population has grown up upon the Waste of several hundred souls with houses built closely together wherever a spot of ground could be safely enclosed … a population now of nearly 600 is all comprised within the space of a quarter of a mile.

2. This was broadly true for the Green itself, with a few exceptions, but occupation of areas around the Green goes back very much further.

It will be difficult to point to any other instance where a population has been collected so rapidly by illegal means and with so little resistance on the part of the owners of the soil”. He argued that the church at Hazlemere, in whose district Tyler’s Green had been included in 1854, was too far away, “a walk of more than four miles over a bleak and exposed heath”, and that the Vicar of Penn had already too much on his hands to look after Tyler’s Green’s “half civilised natives” in whom he saw the features of “social degradation and spiritual destitution”. The new Church would be “visible to every Cottage and every Cottage under the eye of the Minister”.

These were the arguments which he was to put to the Dean and Canons of Windsor “far from intending to cast the slightest reflection upon them but still the fact remains … ” and suggesting that as Lords of Bassetsbury Manor they held some responsibility for what they had allowed to happen and should feel more than usually obliged to contribute generously towards building a Church.

Earl Howe

By far and away the person of most local consequence was the first Earl Howe, whose grandfather on his mother’s side had been the famous Admiral of “The Glorious First of June” in 1794. Earl Howe had inherited his large estates in 1820 and had been Lord Chamberlain to Queen Adelaide, William IV’s Queen, as well as having important political connections. He was a generous man who had set up three schools in the Parish of Penn and built the Church, Parsonage and School at Penn Street (which cost him over £7 ,000). As Patron of the living of Penn, his support was vital if any part of Penn Parish was to go to the proposed new Ecclesiastical District of Tyler’s Green. Thus the first letter on the voluminous files of correspondence is one in March 1852, from Rose to Lord Howe, asking for an interview and for “your Lordship’s support of the scheme without which I could hardly venture to embark on it”. Rose was persuasive and Lord Howe gave his entire approval.

Vicar of Penn

However, he was not so fortunate with the Rev. James Knollis, then an old man of 76, who had been the Vicar of Penn for the previous 30 years. Having just lost a large slice of his parish to the new Church at Penn Street, he was, understandably enough, not in the least inclined to see the process repeated and he dug his toes in about the boundaries, exasperating even the benevolent Lord Howe (who was suffering from gout at the time), “my poor old friend has for the fifth time changed his mind … the very strange conduct of my excellent friend Mr Knollis places me in an unpleasant position”. Eventually the beleagured Mr Knollis offered up only “the 51 households on the Hill” i.e. from Potters Cross up Dog Hill and so the question was effectively shelved until his death in 1860, and the plans went forward on the basis of the 529 on the Wycombe side, alluding only to the Bishop’s intention of eventually including some part of Penn. The final boundaries were not agreed until 1863.

GETTING UNDERWAY

The Committee

PHILIP Rose formed a Committee of all the Patrons and Incumbents of the parishes involved i.e. of Penn, Hazlemere and High Wycombe, together with the Vicar of Penn Street who was about to become Archdeacon, the Rural Dean, two local landowners and his brother William Rose. Lord Howe and his eldest son Lord Curzon, who was living at Penn House at the time, added the necessary weight to the list, although “we cannot of course hope for your Lordship’s presence” wrote Rose humbly to Lord Howe.

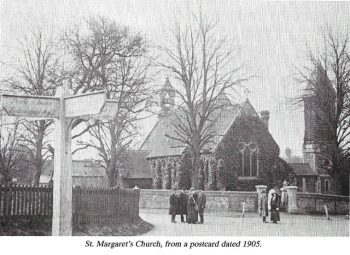

The meetings were held at Rayners and Lord Howe readily agreed to give a “small piece of meadow land at the corner of Hammersley Lane fronting the Green”3 which the Committee quickly identified as the most suitable site for a Church. Philip Rose gave a small addition to it. The cost of “a plain Church, Parsonage House, Schools and Endowment for the living”, was estimated, “assuming a careful and businesslike attention to details”, to be about £4,000, including £1,200 apiece for both Church and Parsonage House. Rose had been highly successful in raising funds for the Brompton Hospital and Chapel and promised he would “strain every nerve to collect what is needful … I have many friends who have promised to assist-some of them are large givers”.

3. A reference in an 1803 deed of a neighbouring property, confirms Mrs Becher’s statement that the Church was built on the site of an old brick kiln.

The Appeal

A printed appeal was sent out to 134 of his friends and local landowners, with Rose contributing the first £500. The response was very disappointing and the subscription book marks many as “refused”, “half promised”, “no answer” and even “dead”. As we shall see later, a shortage of funds bedevilled the enterprise from the start.

The Architect

The Architect, appointed in December 1852, was David Brandon of London. He was then 38 years old, two or three years older than Rose and of Jewish parents. His obituary in 1897 records a most distinguished career. He was Vice President of the R.I.B.A. and was awarded a bronze medal for his services to the Great Exhibition of 1851. He designed some major buildings in London, including the Junior Carlton Club and built a long line of country houses for the nobility. He had made a study of mediaeval work and the church he designed mainly follows the Decorated style of the early 14th C. – as does the church at Penn Street. His task was not only to design a church for 250-300 people and produce detailed drawings and specifications, but also to supervise every detail of its building, attend all the Committee meetings, authorise payment of bills, and advise on all its fitments. He received 5% of the contract value for his services.

The First Curate

Meanwhile, Rose obtained a license and paid half the salary, for a curate, the Rev. Harry M. Maugham, to hold divine services in the Schoolroom (now Tyler Cottage just below the churchyard) which he had established entirely at his own expense, “under a pious Schoolmistress”, in 1846 and was very encouraged by the overwhelming response-“There were 129 persons last Sunday evening with 10 or 15 at the windows in a room that should only hold 30 or 40”.

Advertising for a Clergyman

By June, it was already clear that subscriptions were coming in very slowly and it was decided to advertise for a clergyman “of sufficient private means to be indifferent to stipend” who, it was hoped, could contribute some capital. The great emphasis placed on the “bracing climate” of the area and its healthy nature reminds us what importance such a factor was given in those pre-medical days. Only one of 16 clergymen actually made a firm offer and a word of warning from a friend of Rose’s swiftly followed about him. It was to be another year before a suitable candidate was found.

BUILDING

Contract with W.M. Peniston

THE contract for building a Church for 150 adults and 50 children-smaller than originally planned but” ornamental rather than plain in character” -was not put out to tender, since Brandon advised that if they did so, there would be “little chance of getting the roof on this year”. Instead, it was placed with W.M. Peniston, who was the contractor for the new branch line railway then being built at Rose’s initiative, by the Wycombe Railway Company, from Maidenhead to Wycombe.4 Rose’s firm, Baxter, Norton, Rose were the solicitors for this venture so he must have known Peniston well. The contract for the Church was based on the one used for the Brompton Hospital Chapel, but Peniston requested the rather unusual provision “that materials (being sound) may be used in the work notwithstanding that they may have previously been used on the railway”. By the end of July he had begun to make “vigorous arrangements”. His contract was for £1,350, to be completed by 1 August, 1854.

4. Maidenhead or Slough were the nearest stations until this branch line was opened by the end of 1853. By June 1854, Rose was writing to Brandon “if you wish to return on Saturday afternoon I will arrange for the Engine which usually conveys me to Loudwater to be waiting there to take you back to Maidenhead.” By September there were five trains daily to Loudwater, “a pleasant walk of one and a half miles up a steep hill to my house.” Return fare to London cost 7/1d.

Zachariah Wheeler

Peniston had to sub-contract seven tradesmen to carry out the specialist work. The first to be involved was Zachariah Wheeler (many of his descendants still live locally) to do the foundations and the walls which were specified to be of reduced flintwork with an internal half brick lining. They are over 2 feet thick. His work had to be “fully equal to that of Penn Street and Prestwood Churches”. Coal ash mortar was required for pointing the flints-this is much darker than the ordinary and cheaper chalk lime mortar. When Mrs Violet Becher came to Tyler’s Greenjust after the First World War, she would have known people who remembered the church being built and she records that “the Church was built of chalk flints found in Common Wood together with some black flints which came from Clay Street. The sand was dug from Tyler’s Green Common”. Zachariah Wheeler promised to get the building covered in three months and within a few weeks the foundations had been laid and the vault, which Phi lip Rose intended for his own family, had been dug.

LAYING THE FOUNDATION STONE

INVITATIONS for the laying ofthe Foundation Stone on 8 October, 1853, were sent out only a few days beforehand, an indication of the excellence of the postal service which allowed a reply to be received by the next day. It was intended to place an inscription recording the event, together with a glass jar containing an example of every coin of the Realm dated 1854 (the year in which the Church was to be consecrated), in an aperture under the stone. The text of the inscription was only decided a day beforehand, at which stage Philip’s younger brother Henry, was still desperately trying to get the coins, eventually succeeding at the eleventh hour via “a connexion of the senior clerk of the Mint”.5

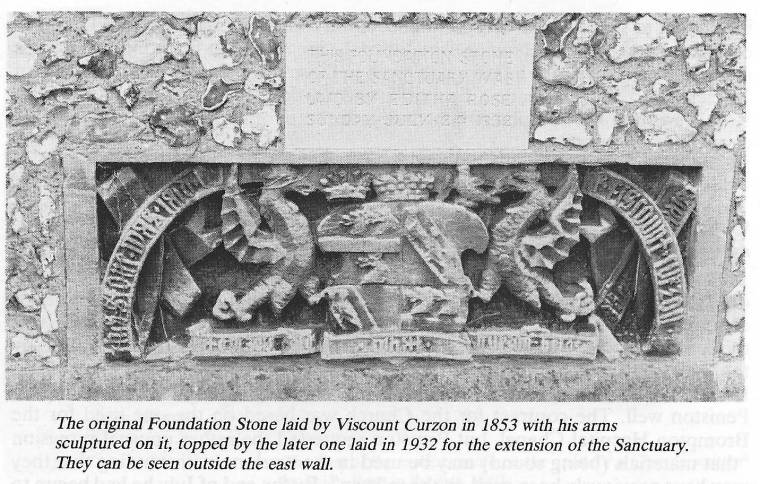

All was ready on the day, which dawned overcast, but was sunny for the ceremony at 1 p.m. The Sunday School Scholars from Tyler’s Green, Penn and Hazlemere had been practising their hymns and were ranged on the walls of the building which were already a foot above the ground. Meanwhile, a procession was formed at Rayners, with the Archdeacon and Rural Dean heading the local clergy, all in their robes, followed by Lord Curzon, Earl Howe’s son and heir, who was to lay the Stone (it has his arms sculptured on it), Brandon the architect, carrying a silver trowel, the builder, carrying a mallet and level, then the other lay members of the Committee, including Philip Rose.

After the ceremony there was plum cake for the children and lunch at Rayners for the visitors, who included Mr and Mrs Benjamin Disraeli. Torrents of rain soon followed. The Archdeacon wrote afterwards to Rose “You have the satisfaction of knowing that all passed over extremely well”.

- When the Church was extended in 1932 the coins were found and cleaned and framed to be hung in the Vestry. A fresh set of coins, dated 1932, was buried under the new Foundation Stone.

PROBLEMS

Peniston’s Bankruptcy

THE ensuing year was not an easy one. Subscriptions were very far short of what was required and not nearly enough even for the Church alone. Only six days before laying the foundation stone, disaster had struck. It was learned that the contractor, Peniston, was in great financial difficulty and some weeks later he was declared bankrupt. Brandon advised that the walls, which were then up to about seven foot, must be covered up for the winter to prevent frost damage, since there was no time to make another contract before the winter. Zachariah Wheeler duly reported “on the Work don at the tilend green church … the church his all most thatcht in and it will be quite safe”.

A New Contract

In January, 1854, five firms tendered for a new contract and the lowest bid of £ 1,150, by Hopkins & Roberts of Islington, was accepted. The highest bidder asked for £2,200. The job was to be completed by 1st September, 1854, with the same specifications as before, which required the stone to be carted from Maidenhead station. Bath stone from the Corsham Down Quarries was to be used for most of the ornamental dressings, Portland stone for steps and York stone for paving. The timber was to be “the best Dantzig Riga or Memel Fir perfectly dry and well seasoned”. By May, the timbers of the roof were on and various skilled tradesmen were involved, including a stone mason, a carpenter, a joiner, a smith, a plasterer, a painter and a glazier.

A labourer was paid 3/6d per day or about £ 1 per week whilst a bricklayer got 4/6d per day. 1,700 bricks cost £3. A bid by Edmund Hancock for the carpentry work had previously been accepted by Peniston and he must have been well thought of since he was the only local man invited to tender for the whole contract the second time around. He may have subcontracted for Hopkins & Roberts but there is no record of who did so.

The Curate

Meanwhile, the Curate was causing trouble. “I am glad the Maugham storm has blown over”, remarked Charles Lloyd, the refreshingly irreverent Rural Dean. But the following April, Rose was writing to the Rev. Allan of Hazlemere, “I think we may mutually congratulate each other on the departure of Mr Maugham. Never did anyone in his position create so much trouble, ill feeling and annoyance as he did during his short sojourn”. Quite what happened is not clear, but there were to be no more divine services in Tyler’s Green until the church was consecrated.

Two months later, it was the Rev. Allan’s turn to be in disfavour, after he had unwisely suggested that Philip Rose was neglecting the needs of Hazlemere. The vehemence of Rose’s 16-page denial concealed a guilty conscience, since only a few weeks earlier he had written “Hazlemere has little claim upon me, Mr Allan himself none”.

Patronage and Endowment

The other major difficulties, apart from funds for the building, were· the questions of patronage and endowment. The Patron had the important privilege of deciding who should be appointed to the living and Rose had persuaded Lord Howe and the Committee that the patronage should be shared between five Trustees, namely the Patrons and Incumbents of Penn and Hazlemere and Rose himself. But it was then found that the Dean and Canons of Windsor, whose collective arm as the absentee Lords of Bassetsbury Manor had been skilfully twisted by Rose, would not legally be able to contribute towards any income for the living unless they held the patronage. This was only accepted by the committee with great reluctance and after

long argument. Henry Rose reported that Mr Knollis “feared that there were very serious difficulties since Lord Howe did not understand the circumstances of the Patronage going from the Trustees”. “Of course for ‘feared’ read ‘hoped”‘, observed Henry laconically. Philip Rose, in a letter to Lord Howe, argued that the most natural arrangement, in view ofthe intimate relationship between Tyler’s Green and Penn, was for them to be held as an integral living with Lord Howe as Patron. Lord Howe’s solicitors saw no impediment in his doing so if he were Patron of both livings.

The First Vicar

It was then that the Rev. Waiter Gibbs, who was to be the first Vicar of Tyler’s Green, appears on the scene. He was highly recommended to Rose by a much admired clergyman friend and was described as “an unobtrusive gentlemanly man of Middle Age, of independent means and without a family, who is seeking an independent charge and is to a great extent indifferent to stipend … well known to the Archbishop of Canterbury and many of the best Anglican Clergy. His wife is said to have a gift for schools and visiting”. Rose took him to Penn to introduce him to Mr Knollis and to afford Lord and Lady Curzon the opportunity of hearing him preach and was immensely enthusiastic. He thought he was “admirably suited for the District and his accepting it may indeed be regarded as the most favourable feature in our whole arrangements “, although he did add on a more doubtful note, “he is Irish and perhaps a little too energetic in his style of preaching, but I think him very well”

The Rev. Knollis on the other hand was not at all impressed and asked that enquiries should be made into his background. “I was made too prominent on Sunday,” commented Waiter Gibbs ruefully, before going on to explain that for 14 years he had been an Incumbent in Lancashire under the present Archbishop of Canterbury, who had given him his first appointment. He then seems to have wandered rather aimlessly for a year or two, which is probably what aroused Mr Knollis’s suspicions. Rose weighed in with an account of Mr Gibb’s unimpeachable family connections. “Mr Gibbs’s sisters are married to men of the highest respectability, one a merchant of standing in the City. Mrs Gibbs was a Haliburton, daughter of a large coal proprietor in Lancashire and has two brother in the army”. Lord Howe’s approval and a letter of introduction from the Archbishop to the Bishop of Oxford, settled the matter and he was taken on as a Curate at Hazlemere pending the construction of the Church. “Is there a canal goes near your place?” enquired WaIter Gibbs “as I have been told that mode of conveyance is cheaper and less liable to breakage than by Rail”. The Gibbs were invited to stay in the Rose’s London house , until the cottage in Tyler’s Green which Rose was lending him, was ready.

THE FINAL DASH

THE building continued during the summer and early autumn of 18?4, without a hitch. The long brIck and flnt boundary wall (“of good sound Birnt BrIcks) around the churchyard, with its three gates, for which Hopkins and Roberts had quoted £372, was eventually built by Robert Hancock and John Tilbury, both local men, for only £90, a matter of great satisfaction to the Committee. Henry Hancock’s bid of £5.10.0d for taking down the cottage in the churchyard was accepted,”the materials to be stacked and reused elsewhere”.

One of the bids refers to ‘Tylers End Green’, as did Zachariah Wheeler earlier, and so it would appear that this form of the name was still in occasional use. . The cottage, “with Woodhouse, Privy and Cowhouse adjoining”, belonged to Earl Howe, who had agreed to its removal, but his tenant, the aptly named John Priest, was loath to move and it was only a desperate plea by Rose to Lord Howe’s agent and an inducement of £10, coupled with the offer of an alternative cottage, that got him out in the nick of time.

A warm air apparatus, “to warm the Church throughout to 65°F”, was installed for £37 and seems to have worked well. It consisted of 27 cast iron pipes inside a brick air chamber, with earthenware pipes and seven iron gratings to emit the treated air.

A barrel organ was installed by G .M. Holdich of London. Rose asked for “one that will grind I should prefer”, pending the later building of a permanent organ. Mr Holdich prepared one “much the same as in the hospital chapel at Brompton, with 13 good Psalm tunes and two chants”.

Thus by early October, Brandon was able to report that all could be made ready for the consecration, given a few days warning.

Legal Documents

However, it was not proving so straightforward to obtain all the necessary signatures to the several lengthy legal documents required. The Deed of Patronage had to be signed by the Marquis of Lansdowne, as the Patron of All Saints, Wycombe, but he was in Germany and despite Henry generously bribing his porter, the Deed was never signed. Then there was some trouble with Lord Howe’s agent over finalising the conveyance of his land for the church, “the most fidgetty man I ever came across” observed Henry. The Committee also had to send out a last minute circular to subscribers about the change in the patronage arrangements.

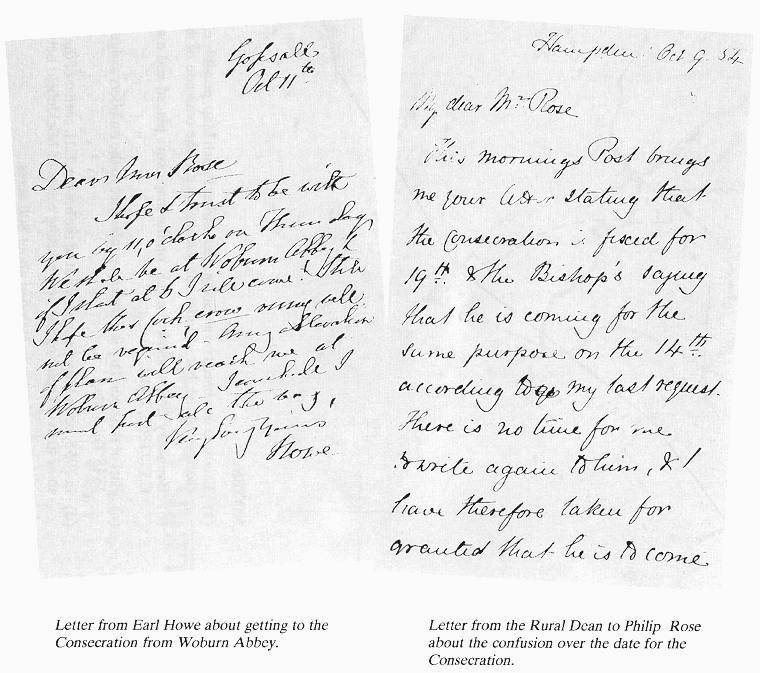

Changing Dates

On 3 October, what must have been a nightmare, began for Philip Rose. At that stage he was assuming the consecration would take place on 14 October, but then he heard from the Bishop that it was to be on the 19th. A few days later the Rural Dean reported, “This morning’s post brings me your letter stating that the consecration is fixed for the 19th and one from the Bishop saying that he is coming for the same purpose on the 14th”. Rose objected vigorously to bringing the date forward at that late stage and so the Bishop, anxious to oblige, moved it back again, but this time to Friday the 20th. Meanwhile, correspondence between the various interested parties was a shambles. A day or two later Lord Howe was still announcing his intention of getting there on the 19th from Woburn Abbey, even though it would mean a “cock crow Rising”.

At this critical stage, Rose fell seriously ill with “a rheumatic affection” which was to plague him at intervals for much of his life, and he was effectively out of action for two months. His brother Henry took up the task of trying to get all the documents completed and his wife also seems to have stood in for him where possible. The Committee met her on Monday 16 October to discuss the detail for the ceremony on the following Friday and to send out the 300 invitation cards which had been ordered only a few days earlier. Late on Tuesday, or more probably on Wednesday morning, by which time the invitations for the 20th must presumably have been sent, the Bishop sent word that he had fixed Thursday 19th at 11 a.m. for the ceremony. One can but imagine the consternation.

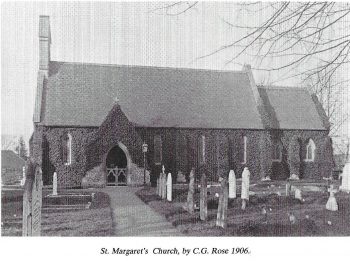

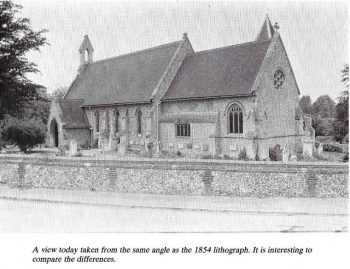

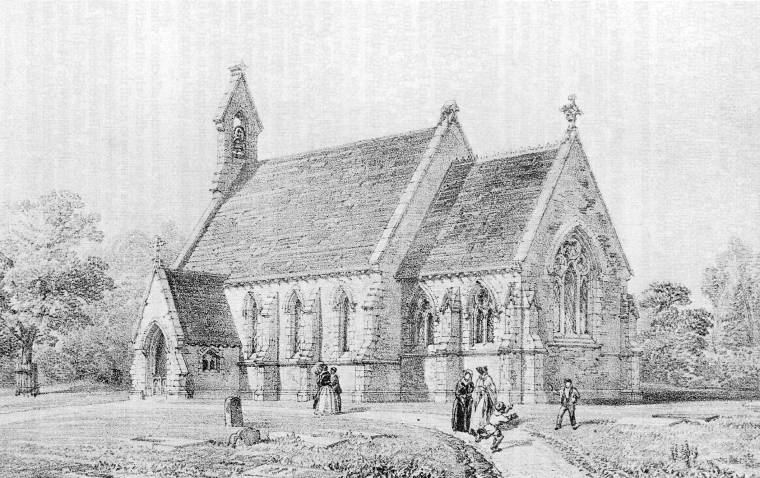

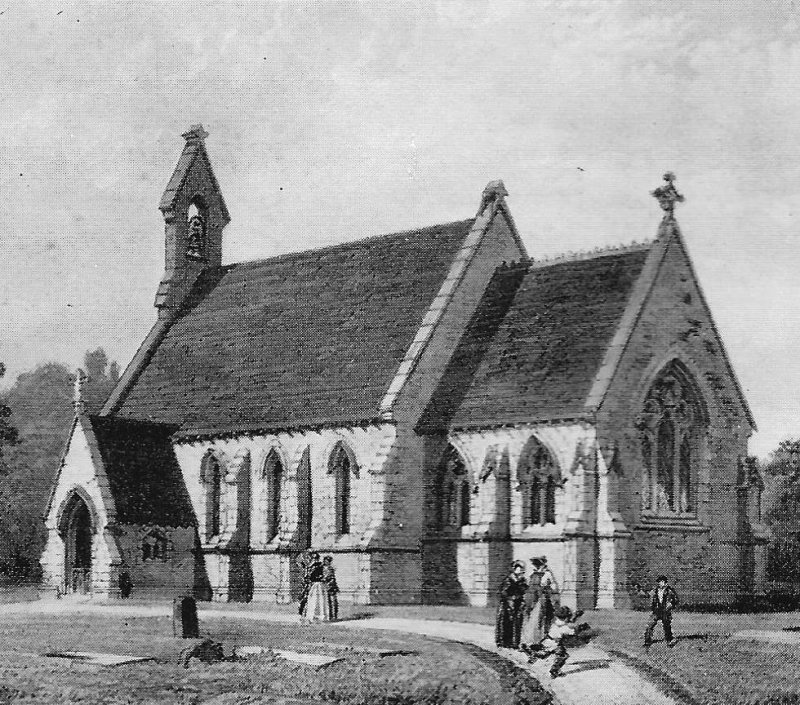

A lithograph of 1854, made before the church was finished and sent out with a second appeal for funds.

A lithograph of 1854, made before the church was finished and sent out with a second appeal for funds.

CONSECRATION

IN the event, the consecration took place on Friday 20 October, but without Lord Howe, Lord Curzon, Benjamin Disraeli or most of the many other friends that Philip Rose would have invited. Apart from the members of the Committee and local clergy, Major Drake of Shardeloes was almost the only landowner of importance noted in the newspaper account of the ceremony. The plan had been for Lord Curzon, who was living at Penn House and Benjamin Disraeli at Hughenden, to house the visitors, supported by the Rural Dean, who in another refreshingly breezy letter had also offered to accommodate “Bishops, Chancellors, Chaplains, Founders and Founders kin if need be”. Rose himself, with what Lord Howe subsequently described as “natural improvidence”, attended the service at which Bishop Wilberforce of Oxford7 gave a “most impressive and eloquent sermon”. The Church was named St Margaret after Philip Rose’s wife. After the ceremony, nearly 80 repaired to Rayners for lunch.

Lord Howe wrote the nicest letter to Philip Rose, which should have been balm to his bruised soul, to say he was glad to hear it had all passed off well and congratulated him on the “termination of a most difficult undertaking owing its commencement and consummation solely to your devoted energy-your best reward will be in the blessing this little church ought to bring”.

David Brandon’s work seems to have been highly regarded, since he was invited the following year to do an inspection and report on Wycombe’s Parish Church and as we shall see later, he was called back again to Tyler’s Green to design the Parsonage House.

7. Until 1845, Tyler’s Green and Penn were still in the diocese of Lincoln, as they had been since Saxon times. The huge diocese was then split up and from then on both have come under the Bishop of Oxford.

AFTERWARDS

Loose Ends

PHILIP Rose was out of action for over two months and there were long delays in tying up the loose ends. Peniston did not receive his final payment until July, by which time the Court of Bankruptcy had threatened to summon Rose to explain the reason for the long delay. WaIter Gibbs was still waiting for the Baptismal and Burial Registers, which is why their first entries are not until February 1855.8 The organ had completely failed the second Sunday after it was put in and Rose had been very upset to hear that WaIter Gibbs had put it aside without consulting him-not unreasonably since he had paid for it himself. “I was entitled to some reference … I find our new Under Gardener is musical and Mrs Rose intends to take him to the Church and practice him in grinding”. “The organ”, he belatedly reported to Mr Holdich, “suddenly gave a cough like a man afflicted with inflammation of the lungs … giving forth such extraordinary sounds … “.

. A brass tablet in the window next to the South door records the death of Martha Holloway. As Martha Janes she was the first child to be baptised in the Church.

The Rose Family Vault

A formal Petition, authorised by the Bishop, leased the vault, which had been built under the north west corner of the Church, to Rose and his heirs for 999 years. All burials were to be in a “leaden coffin”, the vault had to be kept locked up and repairs were Rose’s responsibility.

THE FINAL COST

THE final bill for the Church came to nearly £2,000, compared with Rose’s original estimate of £1,200. Subscriptions, other than from Philip Rose and his immediate family, amounted to only £929, of which £150 was from Lord Howe, another £100 from the Incorporated Church Building Society and £50 each from the Dean and Canons of Windsor and Sir George Dashwood, who “farmed” the Manor of Bassetsbury from them. Lord Carrington, who had some property in Tyler’s Green, was approached but does not appear to have responded. Almost all the other 100 or so subscribers were very modest and Philip Rose therefore had to pay half the total, about £ 1 ,000, as well as lending a cottage, rent free, for the Vicar’s use, until funds to build a Parsonage House could be raised. He also paid half Mr Maugham’s stipend for a year (£25), met all the legal costs, provided a schoolroom and paid a schoolmistress. He claimed later to have met three fourths of the costs.

It had been an expensive venture for Rose, but still more so for Zachariah Wheeler, who was declared bankrupt and for his brother, Thomas Wheeler, who had been “near entirely ruined by his brother Zachariah’s proceedings”.

PART II

ESTABLISHING THE BOUNDARIES OF ST MARGARET’S DISTRICT

THERE is a gap in the record for five years, until May 1860, when the Vicar of Penn, now a very old man of 84, was about to retire after a serious illness. He wrote in a most friendly and dignified way to Philip Rose, who had also been seriously ill, explaining that “Lord Howe has made every arrangement for my comfort”. A few days later he died and the Bishop asked that the opportunity be taken to settle the outstanding question of the District boundaries. The unofficial status of St Margaret’s had limited the unfortunate Mr Gibbs’ income, already small, still further.

He was only getting £30 p.a. from the Dean and Canons of Windsor plus a similar amount from Lord Howe (compare the £50 p.a. of a labourer) and he was not able to hold marriage ceremonies or charge baptismal fees. Added to which, the Vicar of Hazlemere was claiming compensation for those few baptisms and burials that were held in Tyler’s Green. Pew rents, which were im accepted way of supplementing income-a proportion of the pews were allocated to individuals and families in exchange for a yearly rental-were being charged, but only half were taken up, and the number was dropping steadily by 1860. It would seem that the Rev. Gibbs was not the success Rose had hoped for and writing to Lord Howe about further endowments he said, “My own view is that it is extremely desireable that Tyler’s Green should be held by the same Incumbent as Penn9, but then the difficulty arises of Mr Gibbs.” He suggested to Lord Howe that it would be “very desireable to defer making the living too good a thing until it could be seen whether any arrangement were practicable with Mr Gibbs”. Philip Rose’s son, writing in 1900, said “truth compels me to record that the services as conducted by the first Vicar, Mr Gibbs, were no improvement on those we had been accustomed to at Penn Church”.

9This seems to have been a persistent view and was repeated by the Rev. Hayward in 1922.

The Rural Dean wrote to Rose, as “the great promoter of the scheme”, asking him to take the necessary steps to establish the new District, suggesting that “Tyler’s Green as represented or embodied in you must ask for its own legal birth”. The vexed question of the boundary on the Penn side of the Green was tossed back and forth and various compromises discussed. Rose suggested that the proximity of the Green to St Margaret’s argued in favour of including all the Penn side (of what is now Elm Road) in the new District and that the school on the Penn side (where Pond House now stands) would be more efficiently used by the greater numbers in Tyler’s Green. It appeared at the time that neither the Rural Dean nor the Rev. Grainger, the new Vicar of Penn, accepted the argument, which would have reduced Penn from about 800 to under 500 parishioners (there were over 1,200 before Penn Street was removed), but when the bounds were finally published on 12 September, 1863, they took in all that Rose had suggested-proof, if it were needed, of Rose’s formidable power as an advocate and as a master draftsman who could run rings around most of his less practised fellows.

With its legal authority now established, St Margaret’s Marriage Register records its first entries in October 1863.

WaIter Gibbs died in 1862 and is buried under the Altar steps, though his Memorial Stone lies outside the East wall. Soon afterwards, the transfer of the patronage to Lord Howe was confirmed, in exchange for his formal (rather than the previous informal) agreement to augment the stipend by £30 p.a. The patronage remains with Lord Howe to this day.

It may be that in his later years, having successfully bridged the wide gap that society then placed between a professional man and landed gentry, undisputed Squire of Tyler’s Green, secure in his Baronetcy and his close friendship with Disraeli, by then Prime Minister, that Philip Rose wished he had kept the patronage for himself. His son certainly thought it a very great mistake not to have done so, but it is clear his father saw no alternative at the time and in effect successive Lord Howes “practically put the Patronage at our disposal”, records the second Sir Philip.

BUILDING THE PARSONAGE HOUSE

THE Rev. John Power succeeded Walter Gibbs and Philip Rose was informally supplementing his income by a further £30 per annum. Yew Tree Cottage10, which Rose had been lending to WaIter Gibbs, was described as too small and insufficient for any Clergyman with a family. Rose’s original plan, ten years earlier, had been to buy “two substantially built cottages”, known as Caroline and Compton Cottages11 which were then on the market for £600. Brandon had been asked to draw up an estimate to “throw them into one house” adding stables and coachhouse and thought it would cost about £400. This is probably what would have been done had enough money been subscribed at the time.

10 Now greatly enlarged and known as the Red House, next to Rayners Lodge.

11 Later known as the Firs and now as the Old Rectory.

There was no prospect of raising the funds needed for a new Parsonage House from the immediate neighbourhood. The Rev. Power described almost all his flock as being “amongst the poorest of the poor nearly one half during the winter months being in receipt of Parish Relief’. A printed circular was therefore prepared for a wider distribution, with Earl Howe and Philip Rose heading the list with £150 apiece. It raised only a further £180 (including £10 from Disraeli). The Ecclesiastical Commissioners’ policy was to match local subscriptions and so they contributed another £480. This was still not enough, so Philip Rose gave his schoolroom (now Tyler Cottage) valued at £120, as an endowment to the living and this resulted in a further £120 capital from the Ecclesiastical Commissioners. Finally, Lord Howe gave the site, which produced another £200 from Queen Anne’s Bounty.

In July 1864, the way was clear to start building. David Brandon was again the architect and the contractor was Robert Roberts of Islington, one half of the same Hopkins and Roberts who built the Church. The contract was for £1,233, “with no extras whatsoever”, to be completed by 1 May, 1865, with a £10 per week penalty for any delay. The final payment was not to be till nine months after completion. It was a large house (see page 21) with the seven bedrooms, three reception rooms, coachhouse and stables, that were considered appropriate for a Vicar at the time. Later returns also show the addition of farm buildings and piggeries.

GLEBE AND ENDOWMENTS

Gifts of Glebe Property by Earl Howe

NOW that both Church and Parsonage House were built, the remaining problem was to endow the living with land, property or capital, to provide a regular annual stipend for the Vicar.

Earl Howe came to the rescue. In 1864 he had given £300. In 1866 he gave a house and garden- (now Tyler End) with its adjoining cottage, bakehouse and garden, surrounding meadow and orchard, totalling about four and three quarter acres and valued at £700. In 1868 the Rev. Power wrote that “Earl Howe is seeking to benefit this little place in a perfect self-denying spirit of generosity since it is not immediately connected with his own estates in this County”. In 1871 he gave Caroline and Compton Cottages, valued at £700, and two cottages and land (now Dell Cottage), valued at £300. These endowments were matched by the Ecclesiastical Commissioners and produced a further £60 per annum for the Vicar, who now had seven cottages and about seven acres in his glebe property (see page 24), together with two strips of land in New Road which had been awarded to the previous holders of the glebe land under the 1868 St Johns Wood Inclosure Award.

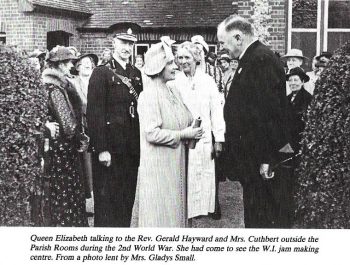

Parish Rooms

In 1886, the second Sir Philip Rose (his father had been made a Baronet in 1874) gave the land on which the Parish Rooms had just been built by subscription, at a cost of £ 1 ,000. The Rooms were primarily for use as a Sunday School but also for “any other purpose likely in the opinion of the Trustees to improve the religious moral and social conditions of the inhabitants of the District”. The “out offices” were to be used as a “Soup Kitchen for the benefit of the Poor Inhabitants”.

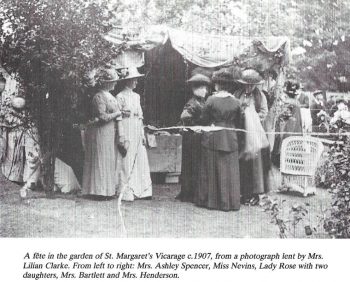

Sale of Glebe Property

Such is the short memory and ungrateful nature of man, that already by 1888, the Rev. Ashley Spencer, in need of money, was writing “I am in the unfortunate position of drawing part of my income from seven small houses or cottages. Three years ago I turned two of the small houses (Caroline and Compton Cottages) into one, and now my new tenant is making conditions … and requires an inside W.C., a kitchen range and new water tanks”. In 1902 he sought permission to give part of the Vicarage garden, which he described as “far too large for any future Vicar’s requirements”, as an extension to the Churchyard where nearly 700 people were already buried. During the First World War he moved out of the Vicarage, presumably because it was too expensive to run, and into Tyler End12. The Vicarage was occupied by Belgian refugees.

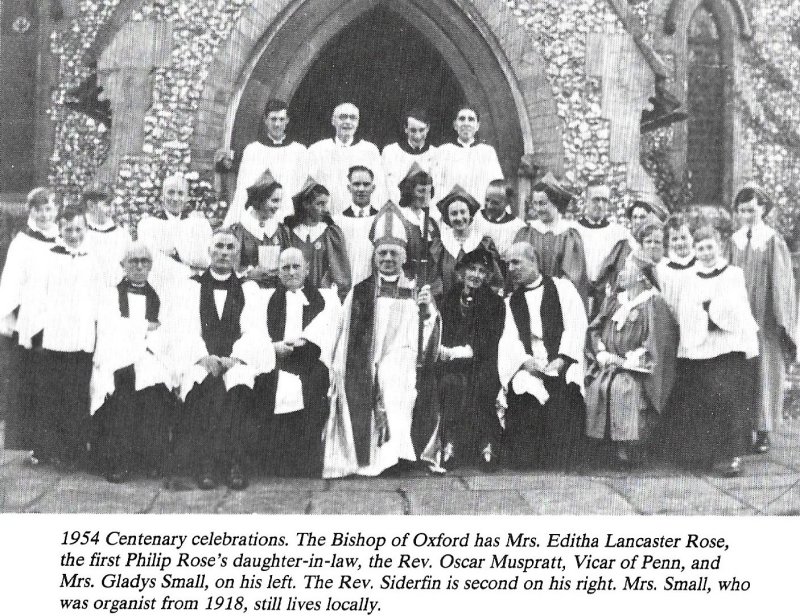

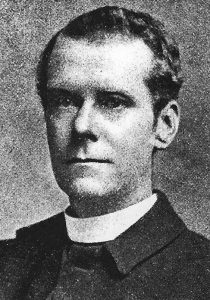

Most of the glebe land was sold by the Rev. Gerald Hayward during his 33 years incumbency between 1918 and 1951. When he arrived in 1918, his income amounted to £289 per annum, including £30 which wa~ still being paid by the fourth Earl Howe, £30 from the Deans and Canons of Windsor and £ 109 from glebe property. But after the First World War there was a very poor return on the glebe cottages, especially with the constant maintenance needed for old brick and flint and with rents of only a few shillings a week. In 1919, five glebe cottages, those now known as Tyler End, Tyler Cottage, and the Dell, with about two acres of ground, were sold by auction for £ 1425. In 1930, land nearly opposite the Wight House (now White House) was sold to Mrs Editha Rose for £250. Part of this land had been allotted to the Vicar and Churchwardens by the S tlohn’s Wood InclosureAward in 1868, for a school “for the children of the labouring poor”, but had never been used for that purpose. In 1932, the two allotment strips on New Road were sold for £165 and houses have since been built on them. In 1951, the ground now occupied by the four new bungalows, very appropriately called Glebelands, was sold for £350, allowing a right of way between The Firs and the Vicarage. In 1952, a part of the remaining Vicarage meadow was purchased by the Chepping Wycombe Parish Council for an addition to the Churchyard which by then was completely full, and in 1959/60, the last of the glebeland was sold off in five separate lots, for only £3,430, as a means of raising some of the money needed to build a new Vicarage.

12 It was then known as Ivy Cottage.

The Vicarage

When the Rev. Hayward had arrived in 1918, he found that the Vicarage was in a terrible state inside and out and that extensive repairs were needed. It was anyway too large and expensive to run, so he therefore let it and lived instead in the Firs13 which was still glebe property. Later, he bought privately and lived for some years in Brown Tiles (now Vicarage Cottage) and then Westbury House, both in Hammersley Lane. Finally he returned to the Firs, where he died in 1951.

His successor, the Rev.J.K. Siderfin, moved into the Firs until the old Vicarage was pulled down and the new Vicarage was built in 1960/61, at a cost of about £9,000. The architect was H.J. Stribling of Slough and the lowest tender, in the curious way of coincidences, was from Messrs. E. Tilbury & Sons, namesakes of the earlier Tilbury who had built the church wall. The Firs, the last two of the glebe cottages so gratefully received in 1871, was sold in 1962.

13.It has subsequently been called the Old Rectory, but Tyler’s Green has always had a Vicar rather than a Rector. ‘Parsonage House’ was used as a more general description of either a Vicarage or a Rectory.

GLEBE PROPERTY

The plan is based on one prepared by Vernon & Son in 1919 for the sale of part of the glebe. Property boundaries often changed when passing from one owner to another, so to some extent the following table is a simplification.

| DESCRIPTION | SHOWN ON PLAN | GIVEN BY | SOLD | |

| (Earlier name is shown in brackets) | PLAN | |||

| 1. Original Churchyard | A | Lord Howe | 1854 | |

| 2. Original Churchyard | B | Philip Rose | 1854 | |

| 3. Addition to Churchyard | C | Philip Rose | 1902 | |

| 4. Vicarage Garden | D | Lord Howe | 1864 | |

| 5. Tyler End (Ivy Cottage) | Lot One | Lord Howe | 1866 | 1919 |

| 6. Glebelands (Lower Meadow) | E | Lord Howe | 1866 | 1951 |

| 7. Vicarage Meadow (Upper Meadow) | F | Lord Howe | 1866 | 1959/60 |

| 8. Tyler Cottage (Schoolhouse) | Lot Two | Philip Rose | 1864 | 1919 |

| 9. Dell Cottage | Lot Three | Lord Howe | 1871 | 1919 |

| 10. Old Rectory (Caroline & Compton Cottages, Then the Firs) |

G | Lord Howe | 1871 | 1962 |

LATER ADDITIONS AND CHANGES TO THE CHURCH

Beautifying the Church

THE second Sir Philip Rose recorded in his Memoir in 1900 that “When the Church was originally built it was very bare and uninteresting. In later years, however, my Father began to be infected with ideas then making great progress, of beautifying, the House of God. An East End Window to the Memory of their parents was erected by my Father and Mother. Then, on the death of an old Friend of the Family, Mrs De Sainte Croix, stained glass windows14 to her memory were erected in the Chancel. At My Brother Willie’s death in 1872 a new Organ was erected in his memory by subscription among those who attended his funeral, and additional stained glass windows were also added by different Members of the family in memory of my Father himself at his death in 1883, and in memory also of my sister, Amy, who died in 1882, and of my Brother Robert who died in 1887. Before my Father’s death, also, he took in hand the embellishment of the interior of the Church, and it was he who erected the fine marble reredos and the marble panelling in the Chancel generally. At my Mother’s death in 1889, my Brother Lancaster and I jointly erected to her memory the small independent Tower with bell turret, containing a peal of eight tubular bells. Anyone who visits the Church as it is now would have a difficulty in appreciating what the Building looked like when first erected and consecrated. Then it was a cold dreary-looking building, without colour or decoration of any kind-now it is one of the prettiest Churches of the Anglican Faith in the County”.

- An architect’s report of 1971 describes the stained glass generally as “very good of its kind”.

Addition of New Vestries in 1922

In 1922, two new vestries were added to the original ones which had consisted of little more than the passageway which now connects the Church with the tower. The funds, over £300, were raised by local subscription and the architect was Arthur Vernon of High Wycombe, who nearly fifty years earlier, as a young man of thiry, had designed our Village School (now the First School) overlooking the Green and three years later the nearby St Margaret’s Institute (now Tyler’s Green House). He also designed Wycombe’s Royal Grammar School.

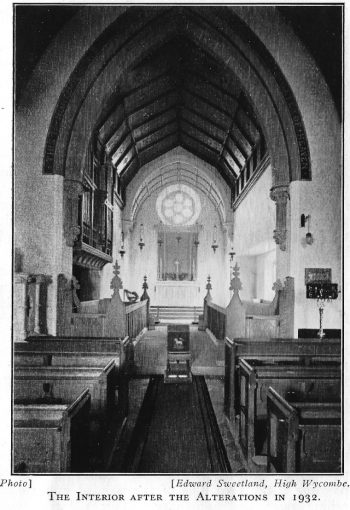

Extension of the Chancel in 1932 15

15. From this paragraph down to ‘The Churchyard Lamp’ is almost all taken verbatim from Mrs Becher’s booklet.

Even on the brightest of days, the heavy colourings of the stained glass windows in the Sanctuary apparently made it impossible to see properly without artificial light-which for many years was oil lamps, faithfully tended by the blind Verger, Mr Tom Burrows, until these gave way to gas and finally electricity. Thus in 1932, the east wall of the Chancel was pulled down and a much longer and lighter Sanctuary, of late 15th C. style, was built, using flints from the same source as in 1854.16 The iron screen to the Chancel arch was removed and a new altar and enlarged choir and clergy stalls were built. The old east window was re-erected in a church in Bethnal Green. The cost of £1,200 was nearly all met by local subscription and the architect was C.H. Biddulph Pinchard, who lived in Knotty Green though his practice was in London. The instruction “Remember Bateman Lancaster Rose” (Philip Rose’s younger son, who lived at the Wight House) is cut into one of the steps of the Sanctuary, in memory of his many contributions to the Church and of the many gifts necessarily removed when the Sanctuary was enlarged. It was his widow, Editha Rose, who laid the new Foundation Stone on top of the original stone laid by Viscount Curzon in 1853 which had been removed to the foot of the new East wall.

16. It is a pity that coal ash mortar was not used, to match the earlier flintwork.

The Altar

The Altar was given by a few friends in memory of loved ones killed in the Great War. It is of Bath stone, carved in panels with a Retable. The spacing and the number of steps follow the traditional order. They are of hewn stone from a quarry near Bath, and are of a lovely rich colour.

The Cross and Candlesticks

These were given with the Altar and are carved out of pieces of oak, four hundred years old, which came from the Belfry of Wells Cathedral when part ofthe interior was restored. The design is silvered over. Later it was found necessary to put stands underneath them, and these small blocks are also made of oak four hundred years old, which came from the Belfry of Holy Trinity Church, Penn.

The Altar Rails

These were given by a few of his old friends to perpetuate the memory of the Rev. R.F. Ashley Spencer, Vicar of this Parish, 1883-1918. They are of oak, and have small figures carved on them symbolic of the Christian virtues.

The Clergy and Choir Stalls

These were the gift of the Rev. M.H. Hayman, in memory of his Father and Mother, who lived at the Firs and lie buried in the Churchyard. They are carved in old brown oak, from trees which have been cut in Thame Park. This particular Buckinghamshire oak, which is very difficult to procure, is of an extremely hard nature and beautiful colour. The Dragons at the foot of each Bench-end are the traditional symbol of St Margaret, the Saint to whom the Church is dedicated, and the carvings on the inside faces of the Poppy heads are her emblem-the marguerite daisy.

The Sanctuary Roof

All the wooden screens and ceilings in the Churches of the Fifteenth Century in England, especially those in the West Country, were painted in tempera colour and gilded; and such painting is the prototype of the painted and gilded ceiling over the Sanctuary. This painting was executed as a voluntary piece of work by five members of the Congregation.

The Pews

In 1934, the pews were scraped clean of the dark varnish with which they had been painted and the result is the beautiful natural colour we see today.

The Porch

In 1935, oak doors were added to the outside arch of the porch in order to enclose it and a four light window was inserted in the south wall of the porch to give the necessary light. This work cost about £80.

The Church Bell

“For many years” wrote an old inhabitant harking back to the days of the first Sir Philip Rose, “there was only one funny little bell to call us to church and the Voluntary was never allowed to commence before the Rose Family from Rayners entered the Church door”. They came via the private footpath from Rayners to the Church, which is still there, marked by a blue door, in Hammersley Lane next to St Margaret’s Close. The bell turret now stands forlornly empty, since in 1960 it was found that the swing of the heavy bell was pulling the turret out to the west. It was therefore removed and installed in the new church of St Andrews in Hatters Lane.

The Churchyard Lamp

It may be of interest to record that the Lamp Post at the Churchyard Gate was given by the Girls’ Endeavour Society, under the leadership of Miss Lydia Barnes, about the year 1906.

The oil lamp was also presented by this Society so that it might be lit every night at 10 pm during the winter when there was no moon. A collection was made yearly throughout the village in order to pay for the oil, and the lamp was faithfully tended by Mr Tom Burrows until the Great War, when all lights were forbidden.

After the third Sir Philip’s death in 1982 his widow refurbished the lamp, which was in state of disrepair and added a plaque in memory of her husband.

The Graveyard

The original graveyard was extended in 1902 and again in 1952 when the Chepping Wycombe Parish Council, who are now the burial authority, opened the new cemetery behind the Vicarage. This, in its turn, is almost full and a large new cemetery at the top of Cock Lane will be opened next year.

Mrs Nancy Dawkins is in the process of carrying out a survey of the graveyard for the Bucks Family History Society, which will show the names and positions of all decipherable tombstones. Copies of the survey will also be lodged with St Margaret’s and the Chepping Wycombe Parish Council.

(With thanks to Peter Stapleton)

CONCLUSION

THE dominant theme that has run throughout this story, has been that of the tremendous energy and drive which Philip Rose bought to bear, forcing himself and others to meet his self-imposed targets, even to the extent of making himself ill in the process. Not for him the breeziness of the Rural Dean nor the humorous asides of his brother Henry.

His motives, as I have already suggested, may have been mixed and his exaggerated deference to those of higher rank and arrogance towards the less fortunate, sound strangely to the modern ear, but we must remember that he was reflecting the prevailing attitudes and realities of his time. There was really desperate poverty, rooted in an almost complete lack of any basic schooling or pastoral care and it is to his great credit that he was one of the few prepared to do something about it. He would have been encouraged by his brother William who was of similar mettle and who as a young doctor and Mayor of Wycombe in 1848, had stood out against all his colleagues in his determination to improve the dreadful sanitary conditions of the poor in the town itself.

Rose’s achievement was very considerable and it was the happy union of his formidable drive with the self-assured generosity and support of the first Earl Howe, that resulted in a Church of which we can all feel proud.

Vicars of St. Margaret’s

| Rev. W.E. Gibbs | 1854 |

| Rev. J. Power | 1862 |

| Rev. E.J. Lowe | 1868 |

| Rev. W.H. Pengelly | 1874 |

| Rev. R.F. Ashley Spencer | 1883 |

| Rev. Gerald Hayward | 1918 |

| Rev. J.K. Siderfin | 1952 |

| Rev. George W. Young | 1967 |

| Rev. Michael E. Hall | 1981-2000 |

| Rev. Mike Bissett | 2003-2020 |

| Rev. Samuel Thorp | 2023 |

The Bell Tower and Ellacombe Chimes i.e. ‘Church Bells’

The bell tower you see today at St Margarets was added to the existing church by the Second Sir Philip Rose in 1899. Whilst there had been a single bell on the far end of the church, that called people to church (after the Rose family had entered) there was nothing more lavish. However on the death of the Second Sir Philip Rose’s mother the Ellacombe bells were installed. “At my Mother’s death in 1889, my Brother Lancaster and I jointly erected to her memory the small independent tower with bell turret, containing eight tubular bells.” The tubular bells are known as ‘Ellacombe Chimes’

The bell tower you see today at St Margarets was added to the existing church by the Second Sir Philip Rose in 1899. Whilst there had been a single bell on the far end of the church, that called people to church (after the Rose family had entered) there was nothing more lavish. However on the death of the Second Sir Philip Rose’s mother the Ellacombe bells were installed. “At my Mother’s death in 1889, my Brother Lancaster and I jointly erected to her memory the small independent tower with bell turret, containing eight tubular bells.” The tubular bells are known as ‘Ellacombe Chimes’

The story of Ellacombe Chimes’ starts in 1817 at St. Mary’s church, Bitton, (located between Bristol and Bath), when Revd. Henry Thomas Ellacombe first arrived as curate. He immediately took a dim view of the bell ringers. He bemoaned that the ringers had the only key to the bell tower’s ringing chamber, and he was aghast that they should flout decent society and only enter the church after the service concluded, so that they might strike up a merry peal. Indeed, the bell ringers would ring whenever they wanted – for any reason and for any sum of money.

Revd. Henry Thomas Ellacombe set to work at inventing his own bell ringing apparatus and in 1821 the first Ellacombe Chimes were installed. Unlike the traditional method of change ringing, where a single person is assigned to each bell and the bells are swung to connect with the clapper. Ellacombe chimes are “hung dead” (remain static) and the hammer moves to strike the fixed bell. Taut ropes are pulled by one person in the same permutations of change ringing, removing the need for change ringers. Success at last, he mused. Rev. Ellacombe would finally gain control of the bell ringing – and the keys to the bell tower.

Around 400 of these mechanisms are still installed in English bell towers, with another three or four dozen sprinkled in countries as far as Canada and Australia.

The original bell turret (seen above) now stands empty, since in 1960 it was found that the swing of the heavy bell was pulling the turret out to the west. It was therefore removed and installed in the new church of St Andrews in Hatters Lane.

Changes since 2010 Including Chancel Re-ordering

In 2010 the chancel was re-ordered to provide a more flexible space for worship and to bring the communion table forward allowing the priest to preside at Holy Communion facing the congregation in line with current Anglican practice. The straight altar rails were made removable to allow use as previously if required and the choir stalls were removed and parts used to create two chairs either side of the altar and a new bookcase for the organist. Part of the chancel floor was raised and a new chancel step created. A new light oak communion table and rail were commissioned as well as chairs and sidetables for minister and preacher and an organist’s screen. The architectural design was by JBKS architects, construction by Billinghurst and furniture both designed and made by Lillyfee Woodcarving Studio. The re-ordering has proven most successful and the increased space has been particularly valuable for baptismal and family services and events such as school and nursery Christmas celebrations.

In 2010 the chancel was re-ordered to provide a more flexible space for worship and to bring the communion table forward allowing the priest to preside at Holy Communion facing the congregation in line with current Anglican practice. The straight altar rails were made removable to allow use as previously if required and the choir stalls were removed and parts used to create two chairs either side of the altar and a new bookcase for the organist. Part of the chancel floor was raised and a new chancel step created. A new light oak communion table and rail were commissioned as well as chairs and sidetables for minister and preacher and an organist’s screen. The architectural design was by JBKS architects, construction by Billinghurst and furniture both designed and made by Lillyfee Woodcarving Studio. The re-ordering has proven most successful and the increased space has been particularly valuable for baptismal and family services and events such as school and nursery Christmas celebrations.

In 2014 a new sound system was installed giving better and clearer amplification of speech, and allowing services to be recorded as well as enabling use of audiovisual equipment.

In 2014 a new sound system was installed giving better and clearer amplification of speech, and allowing services to be recorded as well as enabling use of audiovisual equipment.

In 2016 the organ was overhauled by Mander Organs Ltd (now Wintle Organs Ltd) who had previously rebuilt it in 1969. Following the death in December 2017 of Alan Yeates the much-loved and long serving organist of St Margaret’s a small plaque has been attached to the organ in his memory.

The most recent development has been the purchase in 2018 of a new movable baptismal font purchased with a legacy from Anthea Carter. It is in light oak in keeping with the rest of the chancel furnishings. Most baptismal services now take place at the front of the church with the family and godparents gathered round the font. This provides an intimate atmosphere and it is easier for the congregation to participate in the service.

St Margaret’s continues to evolve to embrace new developments and to serve the needs of the community while retaining the church building’s special atmosphere and remembering its primary purpose as a place of worship and bringing glory to God.

Rear Cover

View the Consolidated Chapelry map as an enlargeable PDF file.

View the Consolidated Chapelry map as an enlargeable PDF file.

See also: Our Ecclesiastical Boundaries