Princess Catherine surrounded by the Hornstein family in the garden at Colehatch House, Penn, England, circa 1940 (Elizabeth Richter)

Catherine Duleep Singh was an Anglo-Indian aristocrat who lived much of her life quietly with another woman in Germany. Then she became a saviour of Jewish refugees.

In November 1938, Wilhelm Hornstein, a government lawyer from Braunschweig, Germany, was arrested by the Gestapo because he was Jewish and sent to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp for several weeks. Lucky to be released because the camp had overestimated its capacity, he emerged, shorn and thoroughly shaken. He fled immediately, without any money or possessions, to London.

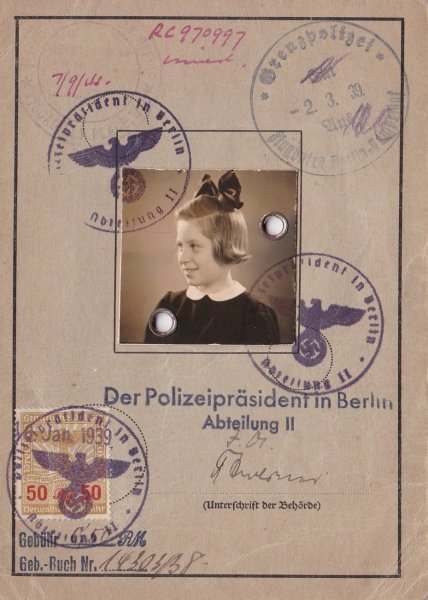

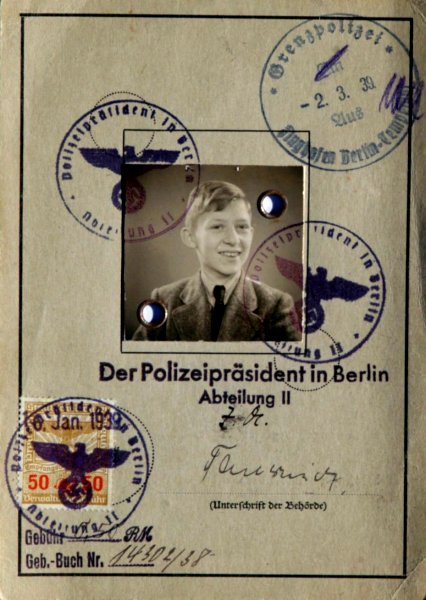

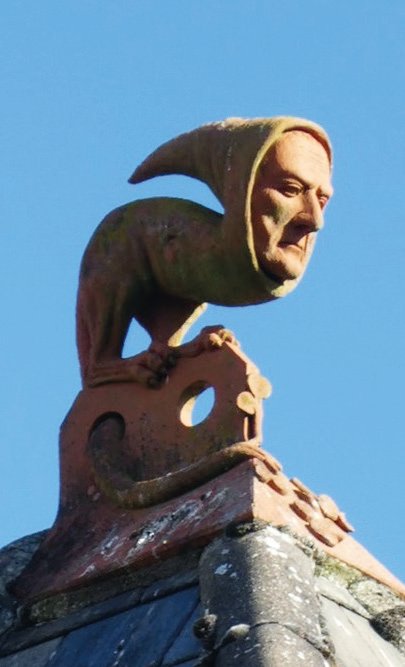

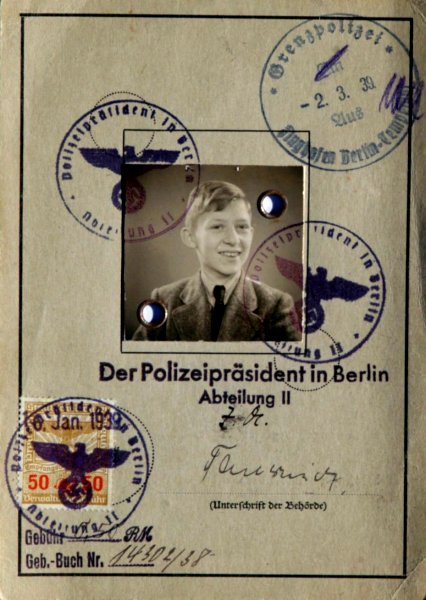

The rest of his family—his wife, Ilse, and their two children, Klaus Georg, age twelve, and Ursula, age nine—scrambled to make exit plans of their own. A Quaker group helped them secure passage to Australia for the following September, but nine more months in Germany felt like an untenable risk. A few days after her husband had left, a despondent Ilse met a kindly old Englishwoman in Berlin. Upon hearing the family’s plight, she spontaneously offered to let all the Hornsteins stay with her in Buckinghamshire until it was time to go to Australia. She promptly arranged visa sponsorship letters—attesting that they would not need financial or employment help from the British state—to enable them all to fly to England. In January, they received new passports stamped with a red letter “J,” for Jude, and on March 2, the three remaining Hornsteins landed at Croydon, London’s pre-war international airport.

The Englishwoman, a tiny, grey-haired lady of sixty-eight, met them there in a light-brown, chauffeur-driven Buick. Ursula had brought her a bouquet of red roses. It turned out to be an apt gift for their host, who was a passionate gardener—as well as, the children soon came to know, a princess: Princess Catherine Hilda Duleep Singh, the English-born daughter of the last maharaja of the once-great Sikh empire, straddling what is today northwest India and eastern Pakistan. “A perfect stranger to do that,” marvelled Ursula, years later, in a series of reminiscences that she recorded with her brother in 2003, when they were both in their seventies. “What you might call a Good Samaritan.”

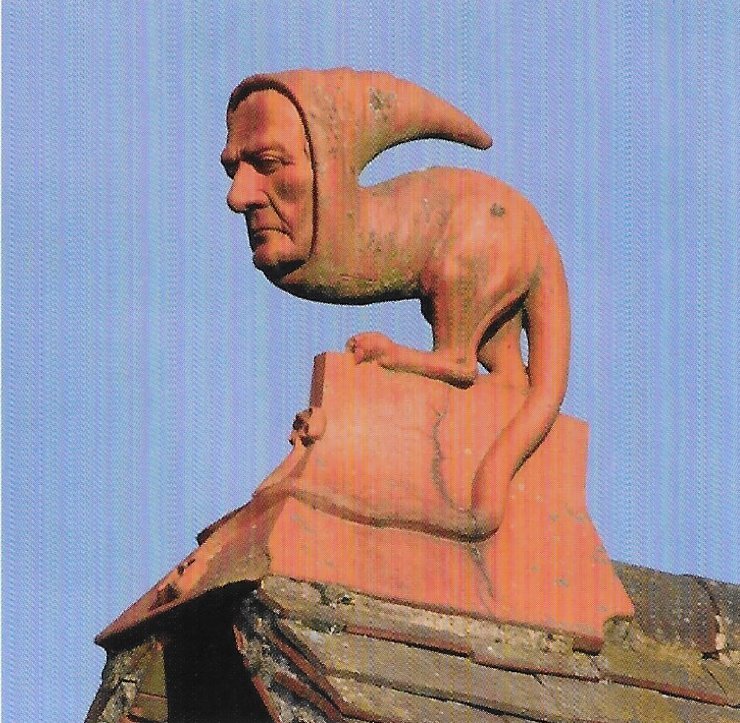

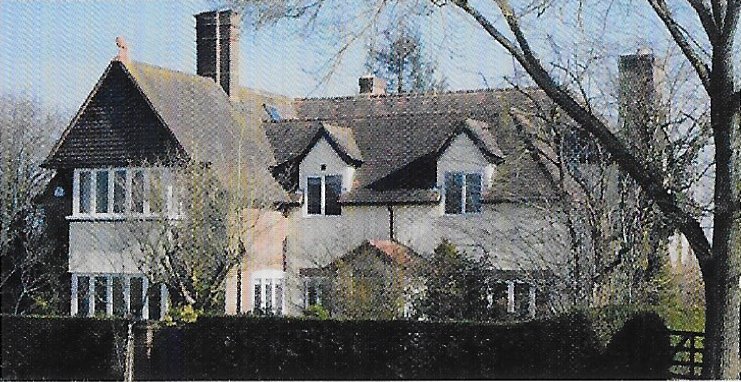

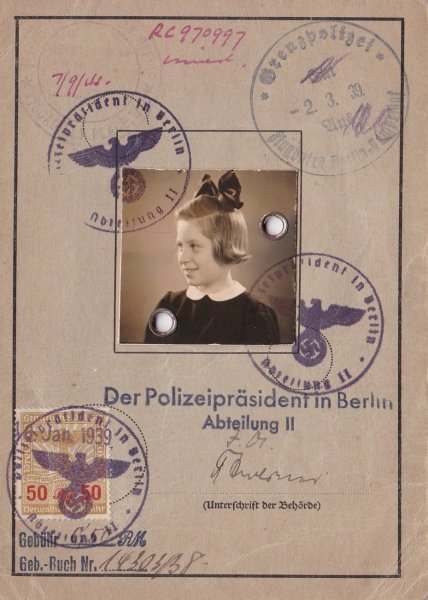

The princess lived at Colehatch House, Hammersley Lane, in Penn, a pretty village perched on a spur of the Chiltern Hills, some thirty miles northwest of London. It was an elongated, whitewalled country house with a clay-tiled roof, set on nearly four acres and framed by neat yew hedges and mature beech trees. A few hundred yards behind the house, the land dropped away steeply where an underground air-raid shelter had been built into the slope. A pair of three-footlong tortoises wandered the grounds, sometimes reposing in a hut the Princess had built for them in her rose garden. She’d bought the property as an investment in 1930, but she herself had moved there only in 1938, when, amid rising xenophobia, she’d had to leave Kassel, the German city where she had spent most of her adult life.

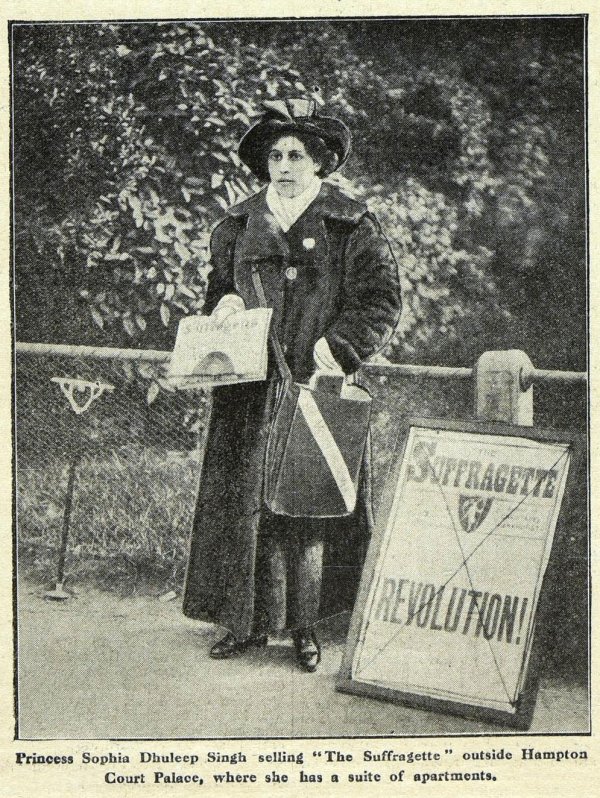

Princess Sophia, Catherine’s younger sister and a former militant suffragette, lived on the other side of the lane, in a cottage called Rathenrea. The aging sisters dined together almost every night, by candlelight—always at Colehatch since, as Sophia’s biographer Anita Anand recounts, Catherine hated the pack of dogs who came from London with canine-crazy Sophia. Ilse, Georg, and Ursula were quickly folded into daily life in Penn. Within weeks, the children were learning English by immersion at the local school, and Ilse started working as an unpaid housekeeper at Colehatch House to earn her keep. (Domestic service was one of the few jobs, alongside nursing and chauffeuring, permitted for Jewish refugees entering England during this period.)

Wilhelm joined them from London, and took Georg on walks down the lane, explaining subjects like the complicated-seeming system of coins — half-crowns, florins, shillings, sixpences, ha’pennies, farthings, and so on—used in England.

Ursula Hornstein, Passport, 1939.

As the weather turned warmer, the princess, who’d never had children of her own, took the Hornstein kids on thrilling excursions. She would pick them up from school in the Buick – “these other children sort of gaping,” as Ursula recalled—to go to the zoo, the maze at Hampton Court Palace, and to the Henley Regatta, where they picnicked on strawberries and cream. “We always used to call her Princess, and she liked that,” said Ursula. “And she used to call me Ursula Dear.” Princess Catherine had, in fact, found a new vocation. Alongside the Hornsteins, she invited more Jewish refugees to Colehatch House. They included a middle-aged German couple whom Catherine had known in Kassel, a doctor named Wilhelm Meyerstein and a nurse named Marieluise Wolff, who had somehow contrived to bring a grand piano with them, which they stored in the damp garage. The princess was alarmed to have an unmarried couple living in her house, and repeatedly urged them to wed, which they eventually did in 1940, in Birmingham. Ursula and George (Georg) believed their whole lives that their mother had met the princess by chance in a doctor’s waiting room, and the story remains family lore today. But I suspect this wasn’t precisely the case, because Marieluise Wolff was actually related to Ilse Hornstein, whose mother was named Alice Wolff. Furthermore, Wolff and Meyerstein both lived in Kassel and knew the princess there. So the Hornsteins may, in fact, have been known to the princess before she became their refugee sponsor, though not as bosom friends, since the children had certainly never heard of her prior to their arrival in Penn.

Soon added to the company were: two Vienna-born Jewish couples in their thirties or early forties, Ernest and Rosa Gutmann, and Richard and Gabriele Reich; several other relatives of the Hornsteins; and a mysterious Jewish violinist from Eastern Europe, whom the neighbours sometimes heard practicing scales in the garden.

Georg Hornstein’s German passport, 1939

The yellowing record of the 1939 National Register (a wartime measure between the official censuses of 1931 and 1941) reports the following residents of Colehatch House: two princesses of “private means,” five “domestic servants,” a research physician, and the Hornstein parents—not even an exhaustive list of the crowded estate but handily the oddest entry in Penn. It was a wonderful summer in their bubble in England, even as, in 1939, Europe edged toward war. One photograph taken at Colehatch in 1939 or 1940 shows a warm backyard gathering of Princesses Catherine and Sophia, Ilse Hornstein, Dr. Meyerstein, the violinist, and one other man around a small outdoor table, all looking up as though interrupted from a long-running conversation. (This and several other photos of Catherine were provided to me by the British Sikh historian Peter Bance, who has spent three decades assembling a monumental collection of Duleep Singh family paraphernalia.)

Their idyll belied the acrimony of the debate over Jewish refugees in the county, Buckinghamshire, at the time. Readers’ letters to the Bucks Herald in March of 1939 complained that Jewish refugees had “ousted British workers from their jobs” and spoke harshly of “those aliens now demanding our misguided hospitality.” The Nazi-orchestrated pogrom of Kristallnacht had occurred a few months earlier, in November 1938. Although this began to raise wider awareness in Britain about the plight of German Jews, the persistence of local prejudice in Buckinghamshire reflected wider public opinion and even national policy: the British government vacillated over the Jewish refugee crisis for most of the 1930s and, as the historian Louise London relates, was still concerned with screening out “the wrong type of [Jewish] immigrants” as late as 1938. It was neither an obvious nor a popular move for Princess Catherine to be sheltering refugees in such a climate.

War finally broke out on September 1st 1939. It became increasingly unlikely that the Hornsteins would ever make it to Australia. No matter—Princess Catherine was happy to let them stay as long as they needed. By the time she died, in 1942, at Colehatch House, the maharaja’s daughter had helped at least a dozen Jews escape Nazi persecution. The question is, how did an aristocratic émigré end up being that Good Samaritan to so many potential victims of the Reich?

I have long been fascinated by Duleep Singh, the last maharaja of the Sikh Empire (in the Punjab), who was brought to England as a teenager and cut a singular path through the Victorian-era Raj. Dispossessed of his kingdom, he became a Christian convert, a personal friend of Queen Victoria’s, a London playboy, a flamboyant East Anglia country squire, and eventually a destitute and paranoid alcoholic who died in squalor in a Paris hotel. But I am even more interested in his children, who each, I felt, inhabited a place in the world distinctly familiar to me: not themselves of the generation that made the epic migration from India to the West, but the naturalized children of that generation—accentless yet foreign-looking—who had to figure out where they stood in a country that they were only provisionally “from.”

Of the maharaja’s seven adult children, I found the fourth, Princess Catherine, the most intriguing, perhaps because she was the most mysterious. She left only ghostly traces in the records about her family compiled by Britain’s otherwise effcient bureaucracy, which—usefully enough for researchers like me, it turns out—created a bas-relief portrait of their movements for posterity. As for the last act of the princess’s elusive history, her remarkable ad hoc refugee program, for years all I could discover of it were a few tantalizing fragments: grainy photos taken in an English garden, news article stubs, and a few German names, with no standardized spelling. Finally, last month, I travelled to England to unearth as much as I could of the episode.

Princess Catherine Duleep Singh was born exactly 150 years ago, in October 1871, at Elveden Hall, a spacious Georgian pile on a hunting estate on the Norfolk-Suffolk border.

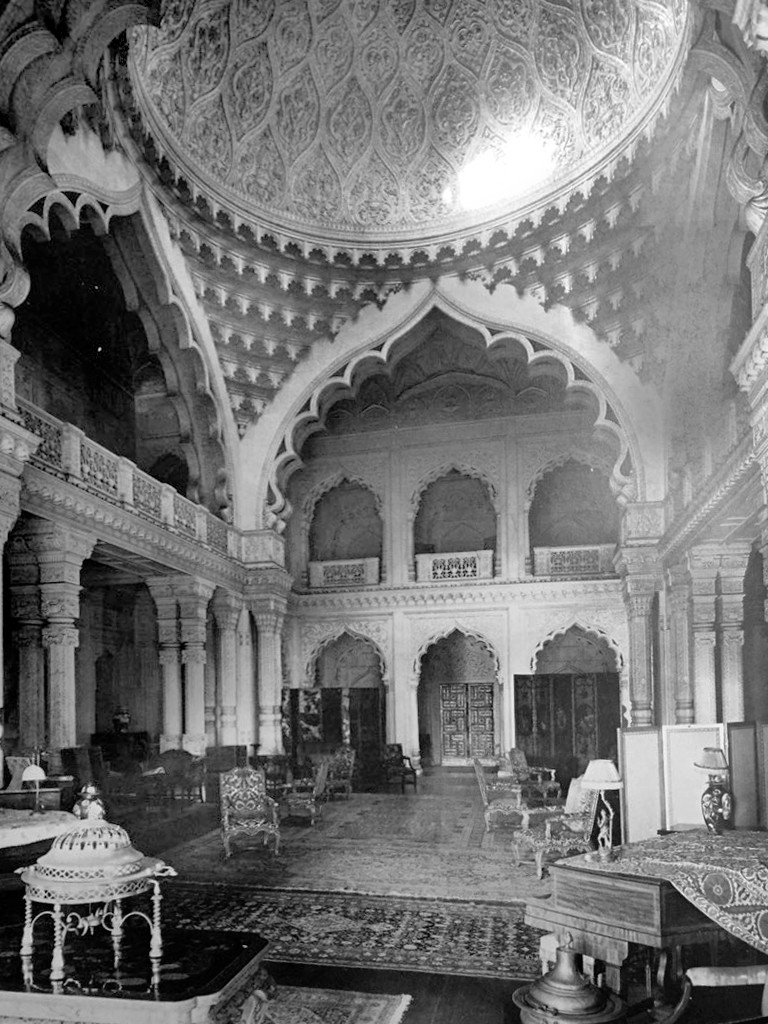

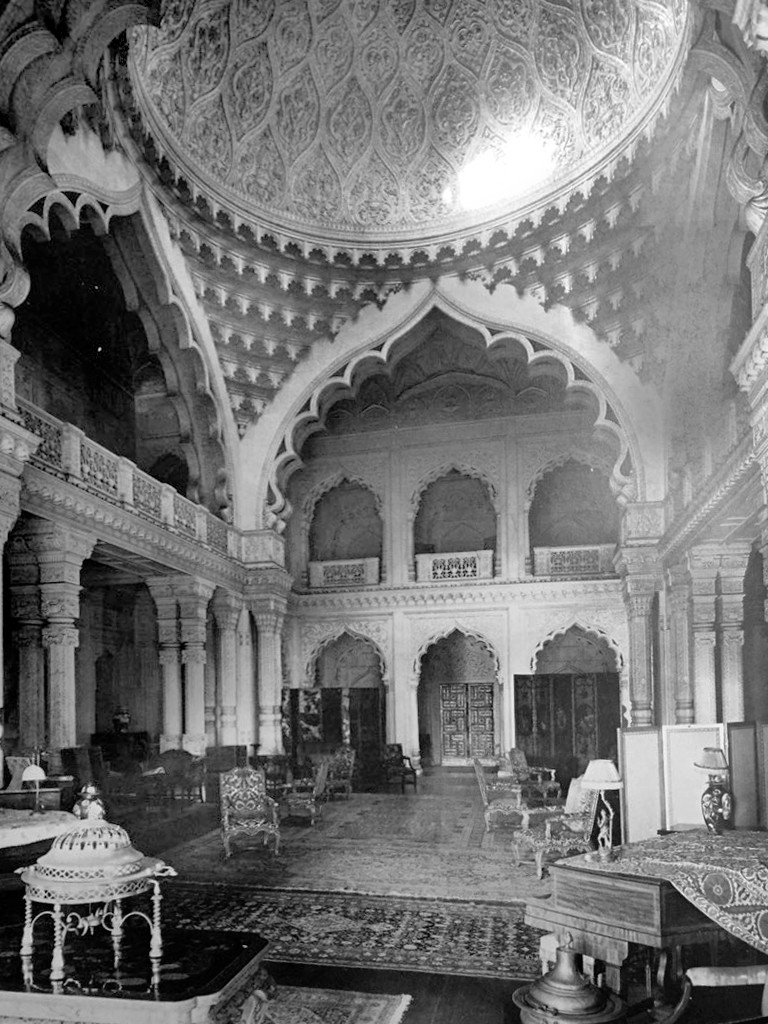

Her father, the maharaja, decorated his residence in a style one might call Mughal Lite, installing plaster-engrailed arches in the drawing rooms, decorating the ceiling with delicate mirrorwork, and importing satin-upholstered chairs with lace antimacassars. His wife, and Catherine’s mother, was Bamba Müller, a convent girl of mixed Abyssinian and German parentage who was a month shy of sixteen when she married the maharaja in Cairo in 1864. She bore him six children at Elveden in quick succession. Catherine was the middle of three sisters, between Bamba, who was named for her mother, and Sophia.

Her father, the maharaja, decorated his residence in a style one might call Mughal Lite, installing plaster-engrailed arches in the drawing rooms, decorating the ceiling with delicate mirrorwork, and importing satin-upholstered chairs with lace antimacassars. His wife, and Catherine’s mother, was Bamba Müller, a convent girl of mixed Abyssinian and German parentage who was a month shy of sixteen when she married the maharaja in Cairo in 1864. She bore him six children at Elveden in quick succession. Catherine was the middle of three sisters, between Bamba, who was named for her mother, and Sophia.

Elveden Hall, Interior

Elveden was less a big house than a small town. In 1881, the estate had over three hundred inhabitants and a school attended by thirty children. There were a collection of hawks from around the world, thousands of pheasants, and even, in a somewhat less successful venture, a few kangaroos. The family, whose children were half-Indian, a quarter-German, and a quarter-Abyssinian, was no doubt unusual in rural East Anglia, but the singular figure of the maharaja, and his sui generis induction into English society by the Queen’s favor, allowed them an exceptional, albeit somewhat eccentric, place in the Victorian social firmament. It didn’t last. By the 1880s, the once-insouciant maharaja grew bitter about his lost kingdom, sank into alcoholism, and abandoned his family, eloping with a chambermaid to Paris in 1886. Bamba the mother died in 1887, when Catherine was fifteen years old. Effectively thus orphaned, Catherine and her sisters were shunted off to makeshift homes, schools, and guardians by the Queen and the India Office. The two older sons—the third, Edward, had died at age thirteen—were not in such desperate straits: they were accepted into institutions like Eton, Cambridge, and the military that helped shepherd them into adult life. But the princesses grew up in a far more haphazard way. In 1890, Catherine and Bamba enrolled at Somerville, a women’s college at Oxford founded just eleven years earlier, where they studied French and German. They gained only middling marks but were assisted by their governess, Lina Schäfer, a thirty-one-year-old German woman from a respectable bourgeois background. It is unclear precisely when Catherine and Schäfer developed a romantic relationship, but both sisters went on holiday with her during term breaks, to such places as the Isle of Wight and the Black Forest.

Catherine was openly devoted to the sweet-natured Schäfer throughout the 1900s, writing of her to her siblings, and sending postcards with their photo together to friends. Their relationship, which spanned forty-eight years, was remarkable not just for its longevity, and for being an openly lesbian partnership in prewar Europe, but also because it was the most enduring and successful romantic attachment that any of the adult Duleep Singh siblings would have.

The impediments to love that they faced were considerable. Their father had once been barred from marrying any aristocratic white European woman, and his children’s marriage prospects were in turn blighted by the ambiguity of their status—admitted to society but never quite of it—which was only compounded by the family’s declining financial straits. Sophia never married or even had a serious suitor. Bamba’s efforts to find a suitable Indian husband came to nought, and when she finally married, in her forties, it was for financial convenience. Freddie remained a lifelong bachelor, leaving no public record of any romance. Victor married an Englishwoman, but it proved an unhappy relationship, scarred by public censure and ended prematurely by his death.

Before all this, though, all five siblings had enjoyed some benefit from the status that high imperial British society—even in its twilight Victorian years—accorded the assimilated highborn of its colonies, especially those who were allowed to use the courtesy titles of “Prince” and “Princess.” In 1891, the princesses’ guardian negotiated with the India Office to secure dowries of £10,000 should Catherine or Bamba ever marry. For reasons unclear, Sophia was not similarly provided for; possibly, since she was only seventeen at the time, the matter was simply put aside.

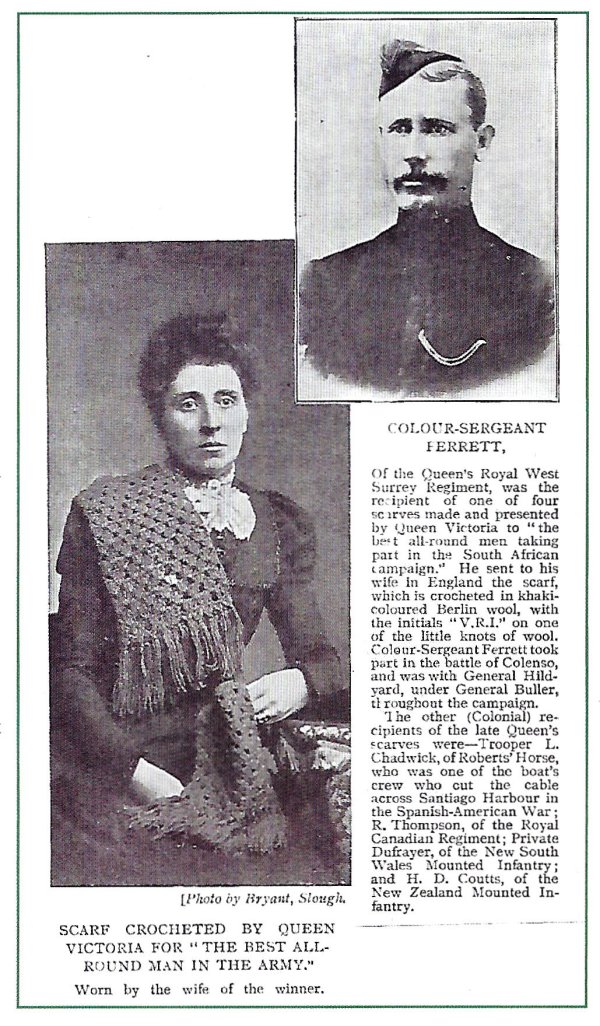

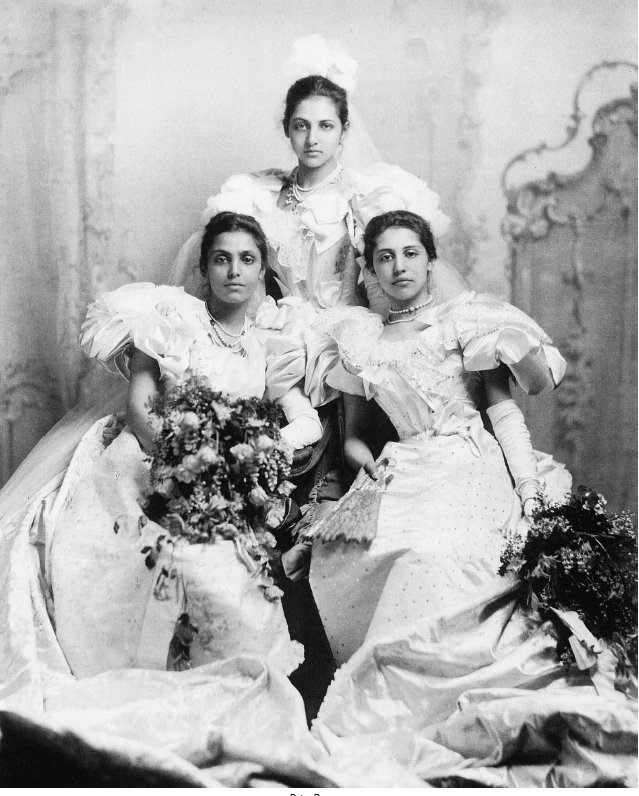

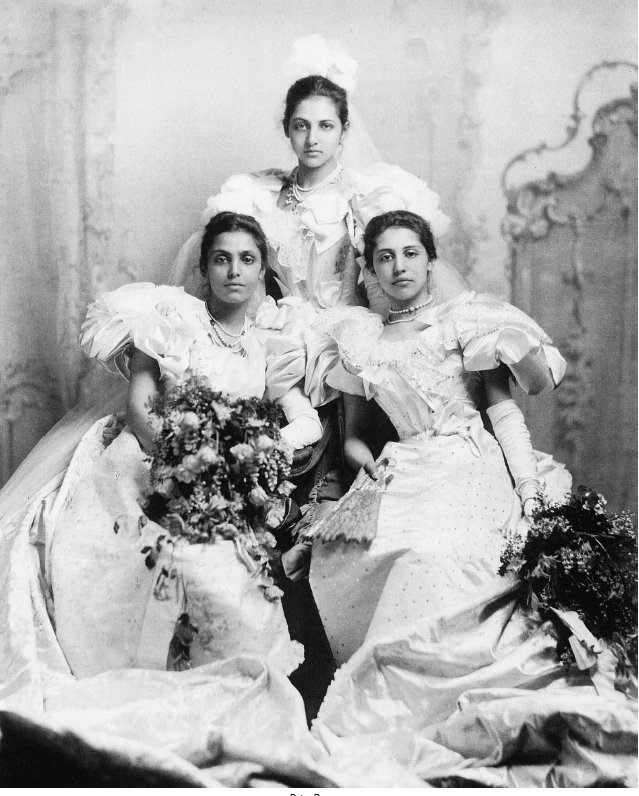

The Duleep Singh princesses (Bamba and Sophia seated, Catherine standing) at their Buckingham Palace debut, London, England, 1895 (Peter Bance)

All three sisters came out as debutantes at Buckingham Palace in 1895, joined London’s upperclass social scene, and were soon fixtures of the court circulars and party pages of their day, albeit with a certain condescension: an 1899 article about Princess Sophia in the Ladies’ Kennel Journal exclaimed that “Strange to say, there are no evidences of the foreign personality to be seen anywhere” at her house at Hampton Court, and a 1901 magazine article marvelled that “notwithstanding her great Oriental name…[Sophia] is to all intents and purposes a thoroughly English girl.” The tone of such press notices carried over even the Atlantic: in 1899, the Boston Herald opined of Prince Victor, who had recently married Lady Anne Coventry, that “he was, if an Indian, as English as education and association could make him.” (In practice, American society could lack the patronizing politesse found in England, as Princess Bamba discovered in 1901, when she briefly enrolled in medical school at Northwestern University in Illinois and was regularly pelted with snowballs by locals.)

Mentions of Catherine on the social circuit grew scarce, however, by the turn of the century. A 1901 magazine article noted that Princesses Sophia and Bamba “have of late years been much seen in Society,” notably omitting the third sister, and a 1904 article in The Sketch confidently stated that “there are two Princesses Duleep Singh.” Instead, Catherine and Schäfer spent most of their time in Germany and settled in a residential colony in the Mulang neighbourhood of Kassel. Their relationship was not reported in the Anglophone press, and it was treated matter of factly in later British political reports, such as a 1918 dispatch from the Foreign Offce blandly observing that Catherine was staying in Germany “on account of the serious illness of her friend [Fraulein] L. Schaefer.” Whether such reticence about characterizing their true relationship was due to polite discretion or sheer obtuseness is hard to gauge. Schäfer bought their house, a half-timbered villa with a large garden at Schloßteichstrasse 15, in 1908, and added Catherine to the lease in 1925.

They maintained a busy social calendar of a somewhat different character in Switzerland and Germany, went to the Bayreuth Opera festival in the summers, and opened a joint Swiss bank account. Catherine steadily refused to marry a man in order to access her dowry (on contrast to her sister Bamba, who eventually married an Australian doctor in Lahore in 1915, when she was forty-six). Catherine was not particularly flush, but she always had an allowance from an 1883 settlement between the India Office and her father. In 1921 she gave this amount in correspondence at around £550 a year; in 1925 she disclosed that it was then less than £400. In one postcard Catherine sent to a childhood governess in 1930, when she was about fifty-nine and Schäfer seventy-one, the pair have grown to resemble each other, dressed in complementary cloche hats and fur-trimmed coats. Over the course of 1930s, however, Nazi inroads disrupted the contentment of their lives in Kassel, as it did throughout Germany. One of their neighbors in Mulang was Felix Blumenfeld, a Jewish paediatrician who was stripped of his medical license in 1933 and forced to work as a trash collector. He committed suicide in 1942. Schäfer, whose health had steadily declined in old age—one of her doctors was the eventual refugee Dr. Meyerstein, a heart specialist—died in August 1938. Amid her grief and the menace of fascism, Catherine packed her bags and relocated to Buckinghamshire.

Picture postcard of Princess Catherine and Lina Schäfer,

Germany, 1930 (Peter Bance)

Catherine’s extant letters do not directly address her decision to accept refugees, but we can make some educated guesses: there was likely a strong element of ‘noblesse oblige’ and an aristocratic disregard for convention, which had always led her to make different choices in life to those of her siblings. Then again, she watched first-hand as Germany slid from xenophobia and intolerance into outright persecution of minorities. It can hardly have escaped her notice that a mixed-race, queer foreigner—even if she was high-born, and even if she would not have used that terminology herself—would be little more likely to meet favour in Hitler’s Germany than her Jewish neighbours.

Although Princess Catherine’s precise motivations can only be guessed at, we do have a remarkable memento of the refugees’ time at Colehatch House in the form of a classified ad that ran in two issues of The Times from May 1939: “Princess Catherine Duleep Singh strongly recommends German Jewish lady Companion-Nurse—Write Box 2546, The Times, 46, Piccadilly W1.” The notice likely refers to Marieluise Wolff, who had worked as a nurse in Kassel. It shows that Catherine did not merely sign paperwork to help Jews leave Germany; she followed through by providing her name as a reference to help these emigrants resettle in England. Her commitment to the people she rescued is demonstrated again and again. When it became clear the Hornsteins were probably not going to make it to Australia, she simply let them stay. She bought young Georg a school uniform (from Harrod’s, no less), and visited “little Ursula” in the hospital when she became sick. She even comforted Ursula when she received hate-filled notes (like “Go home, Nazi”) from anti-German classmates at the local school. After the outbreak of war, thousands of people of German origin were interned on the Isle of Man on suspicion of being “enemy aliens,” a measure that, while temporarily justified on grounds of national security, forced Jewish refugees from Hitler to bunk next to actual Nazi sympathizers. Princess Catherine worked to ensure the speedy release of those she could vouch for. Ms. Wolff’s companion, Dr. Meyerstein, was thus granted “exemption from internment” on October 27, 1939, and his status recognized as a refugee.”

The Princess Catherine with Marieluise Wolff and Wilhelm Meyerstein, at Colehatch House, Penn, England, early 1940s (Elizabeth Richter)

Reichs and the Gutmanns, who were also interned, all listed Princess Catherine Duleep Singh as their employer on their release certificates. Wilhelm Hornstein managed to avoid internment for his family by his enlisting in the British Army’s Expeditionary Force. This was one of the few ways for Jewish men, less likely to find positions in domestic service, to earn money. He served in France in 1940, and later worked for the Pioneer Corps and Intelligence Corps, which were based near Penn, at the Wilton Park estate. There, his job involved interrogating high-ranking German prisoners, a startling about-face from his service in the German army during World War I, when he would have taken orders from such men.

Colehatch House

I was finally able to visit Colehatch House myself on a soggy day this past October. It was renamed Hilden Hall shortly after the Hornsteins arrived in 1939, and that remains its name today. The property dates back to the seventeenth century, while the white farmhouse that the princess and refugees lived in was built mostly in the 1840s. It has been modified further since then, but many of the house’s original features remain: its low ceilings, oak beams, gabled roof, and even an old freestanding coach house.

Catherine’s bedroom looked out onto the backyard. Her balcony has since been demolished, and her room combined with two adjacent ones to make a large suite; what is today a six-bedroom house likely had several more sleeping quarters in her time, which helped accommodate her many guests. The princess died suddenly on November 8, 1942 (it was thought, of a heart attack). She was found by her sister Sophia, who had the door to Catherine’s bedroom broken down after she had failed to appear at breakfast.

She was seventy-one years old. As for her refugee boarders and lodgers, there would be further twists and turns of fortune. Through letters and personal entreaties to the headmaster, Georg Hornstein’s mother won him a scholarship to Rugby, the prestigious private school, which in those years reserved a bursaried place for a refugee. George Horton, as he anglicized his name at school, went on to study physics at Imperial College London, gained a doctorate in physics in Birmingham, then married and emigrated to Alberta, Canada, where he taught and developed a specialty in solid-state physics. He ended up at Rutgers University in New Brunswick, where he spent fifty years as a professor until his death in 2004. He had four children, who were all taught to speak German. The family often drove into New York City, where they stocked up on deli luxuries at Zabar’s and went to the Metropolitan Opera. Ursula stayed in England all her life. She went to secretarial college, then met and married an Englishman named Paul Bowles, with whom she had two sons. After obtaining her teaching certificate in the 1960s, she taught in state schools and, according to her son Michael, was a passionate, lifelong trade unionist.

Wilhelm Meyerstein and Marieluise Wolff sold their piano and used the proceeds to buy a small house in Birmingham, where Meyerstein found a new job as a medical professor. In 1945, Marieluise regained certification to work as a nurse in Britain. George Horton paid them a visit when he moved to Birmingham for his PhD. I came to know these details through a remarkable series of conversations that Ursula and George recorded in 2003 in England. Over the course of five hours, they recounted details of their childhood in Germany, their dramatic escape to England, and their passages into adulthood. One of George’s children, a sixty-five-year-old retired teacher’s aide in Connecticut named Elizabeth Richter, shared the recordings with me after I got in touch with her for this story. Ilse and George were the last refugees to leave Hilden Hall, in 1944—George commuting into London from Penn for the whole of his first year at Imperial College. Lacking Catherine’s personal connection with the family, Sophia had barely tolerated their presence after her sister’s death, so “the writing was on the wall” that they would have to leave, as George recalled, in the tapes. Sophia died in her sleep at Rathenrea, in 1948.

For decades afterward, few people probably gave much thought to the Indian princesses who’d lived in Buckinghamshire, save for a spell in 1997, when Princess Catherine’s and Lina Schäfer’s Swiss bank holding was discovered amid a wider effort to clear up about two thousand accounts that had been dormant or unclaimed since the end of World War II. Penn was briefly abuzz with speculation as to who might inherit the fortune, since none of the princesses had living descendants. The account turned out to hold only about 137,000 Swiss francs—and no Sikh crown jewels or valuable documents—a sum that was ultimately awarded to a Sufi pir, or spiritual guide, who had been a close confidante of Princess Bamba’s until her death, and to whom she left her home in Lahore’s gated Model Town neighborhood. Evidently, the usually scrupulous Princess Catherine had set little store by the money in Switzerland, for her will omitted any reference to it. What it did specifically address, in a codicil, was what to do with her remains.

It took seven years to carry out her instructions, but in 1949, her sister Bamba—by then the last living member of their Sikh dynasty—finally executed Catherine’s last wishes: to take a portion of her ashes back to Kassel, and bury them “as near as possible” to the grave of Lina Schäfer.

Krithika Varagur, a New York-based writer and journalist, is the author of The Call: Inside the Global Saudi Religious Project (2020), an editor at The Drift magazine, and a National Geographic Explorer. In 2020, she was the Newswomen’s Club of New York’s Foreign Correspondent of the Year.

Krithika Varagur ©