Researching the Duleep Singh sisters of Hammersley Lane

The first time I looked, as it were, at Tyler’s Green, it was in bird’s-eye-view photographs of the village through the decades, on a Zoom call with the head of the Bucks Family History Society. Tony very kindly explained to me – an American journalist who had not left the country in nearly two years due to the pandemic – the concepts of the “Home Counties” and a “chocolate-box village,” as well as why certain people of interest to me, namely the Princesses Duleep Singh, may have wanted to live there during World War II. The first time I visited Tyler’s Green in person, in October 2021, I drove, which was an adventure in itself; to this day I don’t quite have the hang of driving on the left. I came there armed with just one name: Miles Green, whom I had called out of the blue on a temporary UK phone number to make a rendezvous. Those of you reading may be well aware that if you make enough inquiries into Penn and/or Tyler’s Green, all roads lead to Miles, at his cottage on the track opposite the primary school where we arranged to meet.

I was, and am, researching the lives of three Indian princesses who lived in Victorian England, daughters of Duleep Singh, the last Maharaja of the Punjab and erstwhile confidante of Queen Victoria. I hoped to learn more about one particularly mysterious episode in the life of the most enigmatic sister, Princess Catherine Hilda Duleep Singh. I knew that after a lifetime in Kassel, Germany, she had returned to the country of her birth, England, in 1938, and spent the last four years of her life at Colehatch House in Hammersley Lane. I also knew, thanks to some fascinating black-and-white photographs, that she had sheltered there a number of Jewish refugees fleeing Nazi Germany. But who were they? How did they get there? What was their life like in Tyler’s Green?

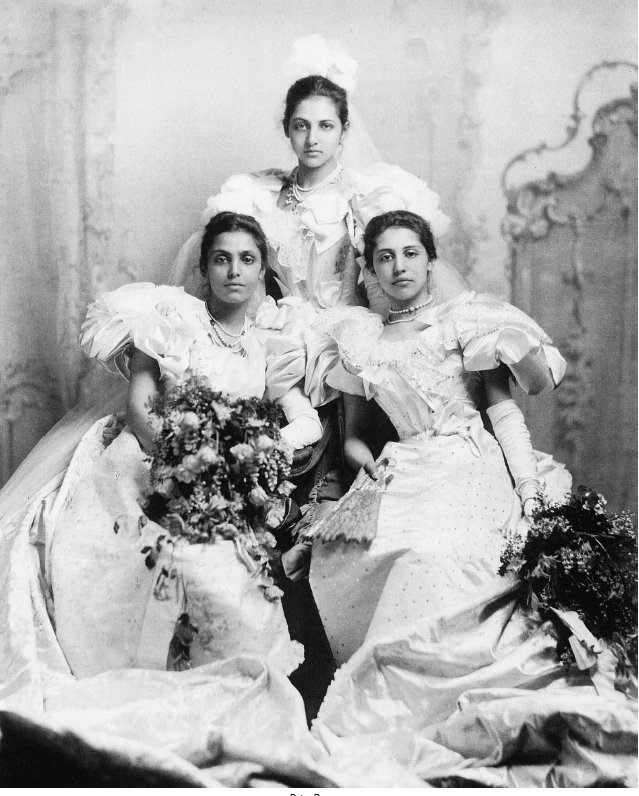

The Duleep Singh princesses (Bamba and Sophia seated, Catherine standing) at their Buckingham Palace debut, London, England, 1895

In our highly globalized and highly digitized age, one imagines everything can be found online. But this is not true. I learned more in a few days in Bucks than I could have over several years in New York. Among other things, I learned the names of at least a few of the refugees, due to the internment certificates from the Isle of Man that Ron Saunders, another eminent local historian, had the good sense to dig up on my behalf. (This is where people of German nationality were interned right after the outbreak of war.) Furthermore, Miles was able to finagle visits to both Colehatch House (now called Hilden Hall) and Rathenrea (now called Folly’s Meadow), where the youngest princess, Sophia, lived in wartime. I could finally explain, for instance, how many steps it would have taken Sophia to come for candlelit dinner on Catherine’s lawn every night. And I could report with authority that on the idyllic grounds of Hilden Hall, there is also a well-preserved air-raid shelter. I am most grateful to the welcoming owners of both those houses.

But that wasn’t even the hard part. Writing any history, but especially one set in a place you are not yourself from, is an exercise in confronting your own ignorance hundreds of times a day. And as I set out to write about Tyler’s Green after my trip, Miles and I had a long correspondence last November speculating on when and why Colehatch House became “Hilden Hall.” One apocryphal story has it that Princess Catherine named it after herself (that is, her own middle name, Hilda), but Miles rightly pointed out that that would have been decidedly un-English. Perhaps, he has suggested, she was influenced by the 1936 publication of The Concise English Dictionary of English Place-names by Eilert Ekwall, which gives the derivation of Hildenborough in Kent as from OE Hildenne meaning ‘Hilda’s denn’, with denn as Old English for “a pasture.” “I can see our Anglicised Princess taking an interest in Ekwall’s new book, which everyone would be talking about, and the perhaps chance discovery that Hilden meant ‘Hilda’s pasture’ and bearing in mind that putting someone out to pasture means retiring them away for the demands of a working life, might well have tickled her fancy and given her the excuse she needed to be so un-English as to name the house after herself.” A much-better informed speculation, I think!

Anyway, I did manage to get to the bottom of who many of refugees were, especially the Hornstein family from Braunschweig, Germany, whom I wrote about in my story for the New York Review of Books, “The Anti-Nazi Punjabi Princess.” In the spring, I sold a proposal for a book that would expand on this work to cover the lives of all three Duleep Singh princesses. And thus I prepared to confront my ignorance thousands if not millions more times in the coming years. In July, I returned on a research trip to England and had a pub lunch with Miles and Ron on one of the year’s hottest days. My main objective was to be gently chided some more, as that is the most valuable possible asset in my line of work. Ron promptly informed me that Penn and Tyler’s Green have two completely different MPs, and Miles pointed out that an Americanism I had used in my piece – “backyard,” rather than “back garden” – was rather out of place. Before I left, I made them both promise to read the drafts of my chapters set in Bucks in a couple of years. I expect they will find hundreds of errors between them.

I feel deeply indebted, as someone writing about Bucks as it was 90 years ago, to Miles, Ron, and all those living in Bucks today. And I am still working to answer quite a few questions about the princesses’ time here, so if anyone has insight on the following, do get in touch.

– What were Penn and Tyler’s Green like in the wartime years between 1938 and 1945? (If any reminiscences from your parents or grandparents were passed down to you, I would love to hear them!)

- What was it like for Jewish refugees in particular during that time?

- I am hoping to get in touch with one “Jacqui Green,” child of Hilden Hall’s housekeepers, John and Janet Lane, who would be in her 70s now… if you have any leads, do let me know.

- Likewise, I am also curious about one Lillian Coram, who lived in the High Wycombe area and who worked for Princess Sophia in Tyler’s Green. She was born in 1920 and died in 2014. If you have heard of her or if she has any children or family of whom you are aware, I would love to get in touch.

You can write me at kvaragur@gmail.com or through my website www.krithikavaragur.com. And I expect to be back next summer, which we all hope will be a couple degrees cooler than the last one.

Until then,

Your privileged visitor,

Krithika Varagur

Brooklyn, New York – September 2022.

First Published in Village Voice No 213 in Dec 2022.